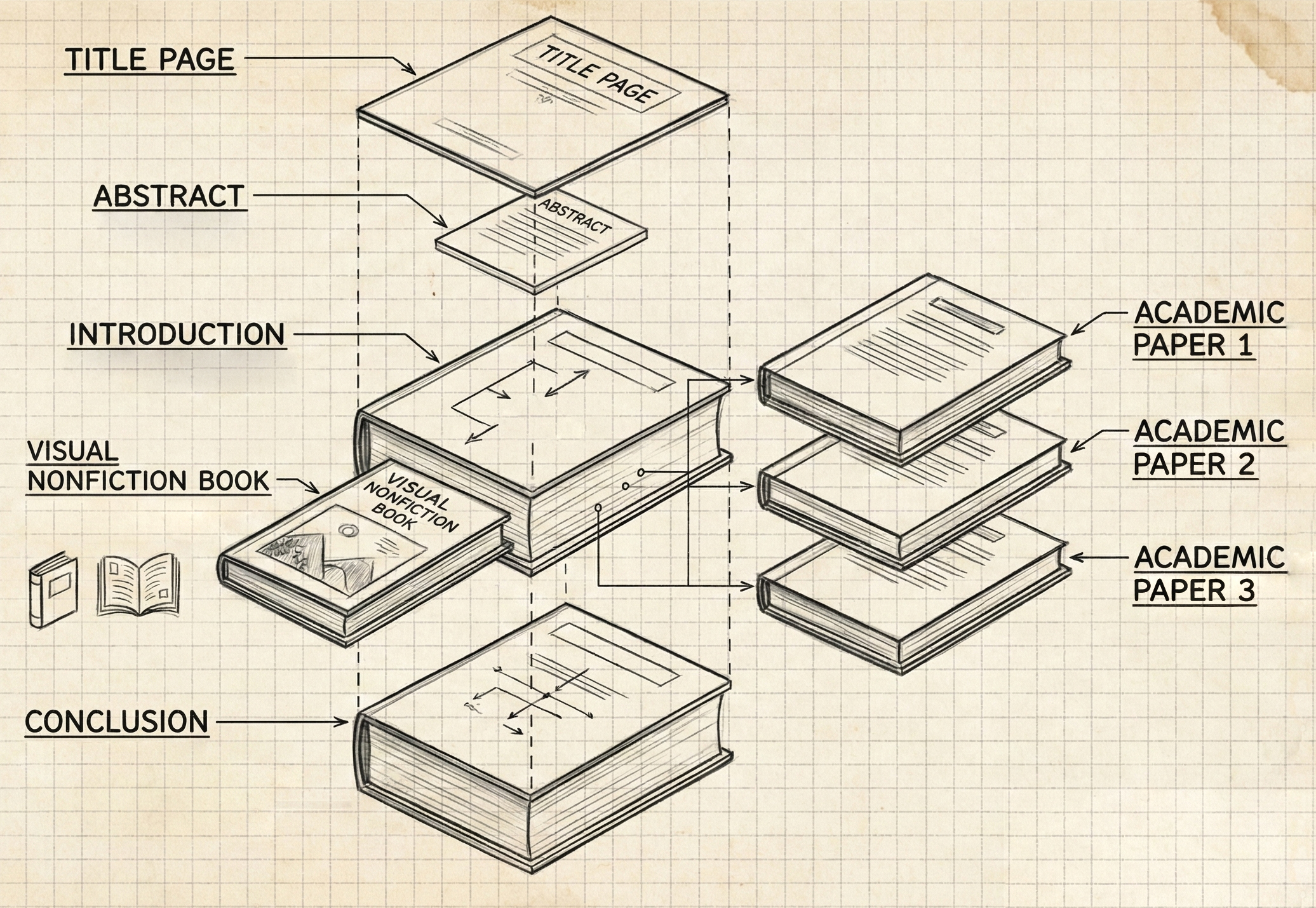

I am exploring the problem space of assessing writing of undergraduate students in a generative artificial intelligent (GenAI) world through a double diamond design process. I first explored the problem space in order to better understand the problem, in Attempting to Define a Wicked Problem, before converging on a singular problem statement, in Converging a Wicked Problem: ‘Good Enough’. While this statement does not fully encompass the entire problem space, it is considered “good enough” for addressing a wicked problem (Corbin et al., 2025):

“How can we make the learning that occurs while writing an essay visible?”

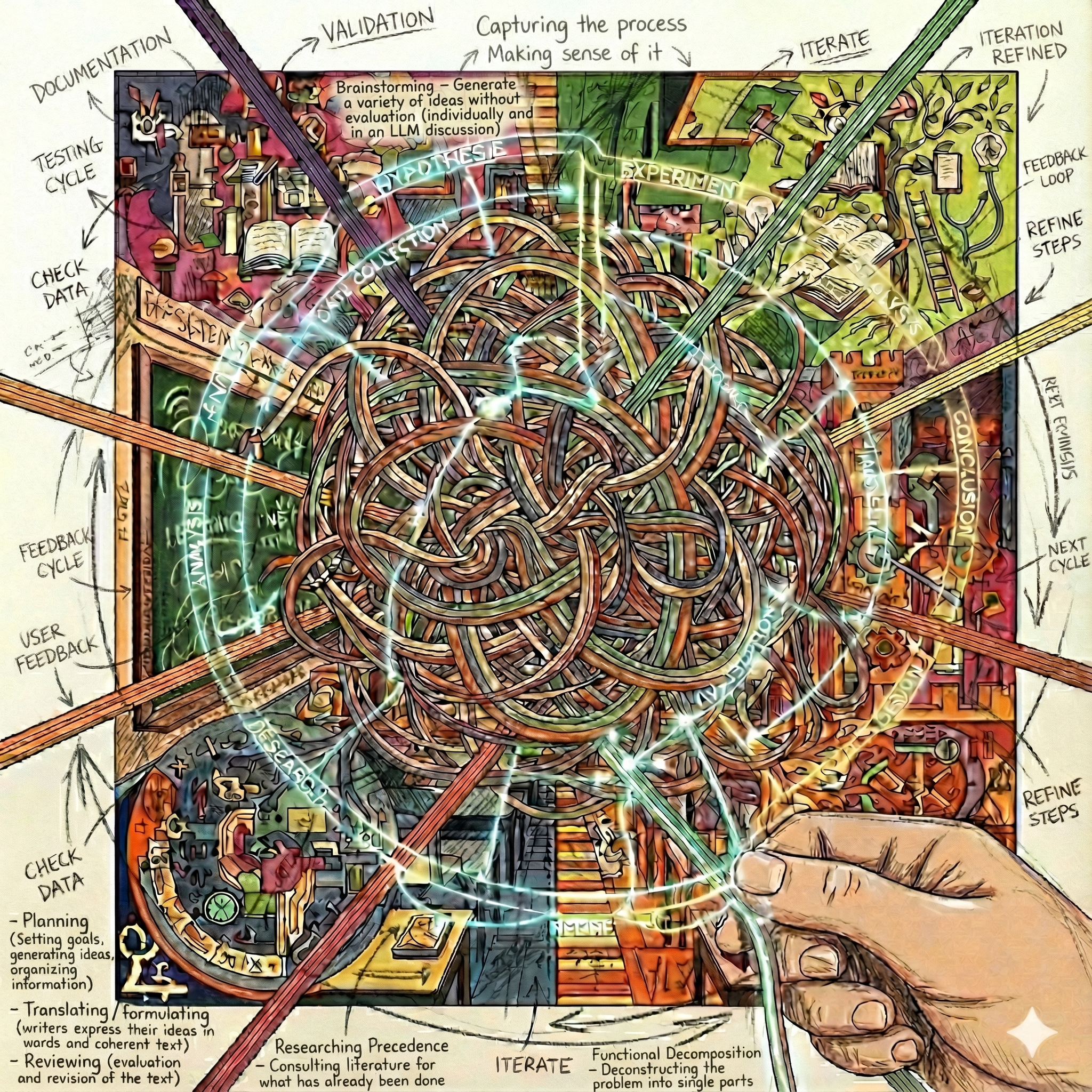

This next step involves generating as many solutions as possible to better understand the breadth of the solution space and move forward with confidence in the direction I ultimately choose. I utilized the following techniques:

- Brainstorming – Generate a variety of ideas without evaluation (individually and in an LLM discussion)

- Functional Decomposition – Deconstructing the problem into singular parts

- Worst Possible Solutions – Consider the worst way to solve the problem (individually and in an LLM discussion)

- Researching Precedence – Consulting literature for what has already been done

I appreciate the self-referential, meta nature of this problem, as I am currently engaged in the very process of making my learning visible, with the explicit aim of demonstrating more than just a final product. This experience has provided me with a unique perspective on the problem.

Ideas

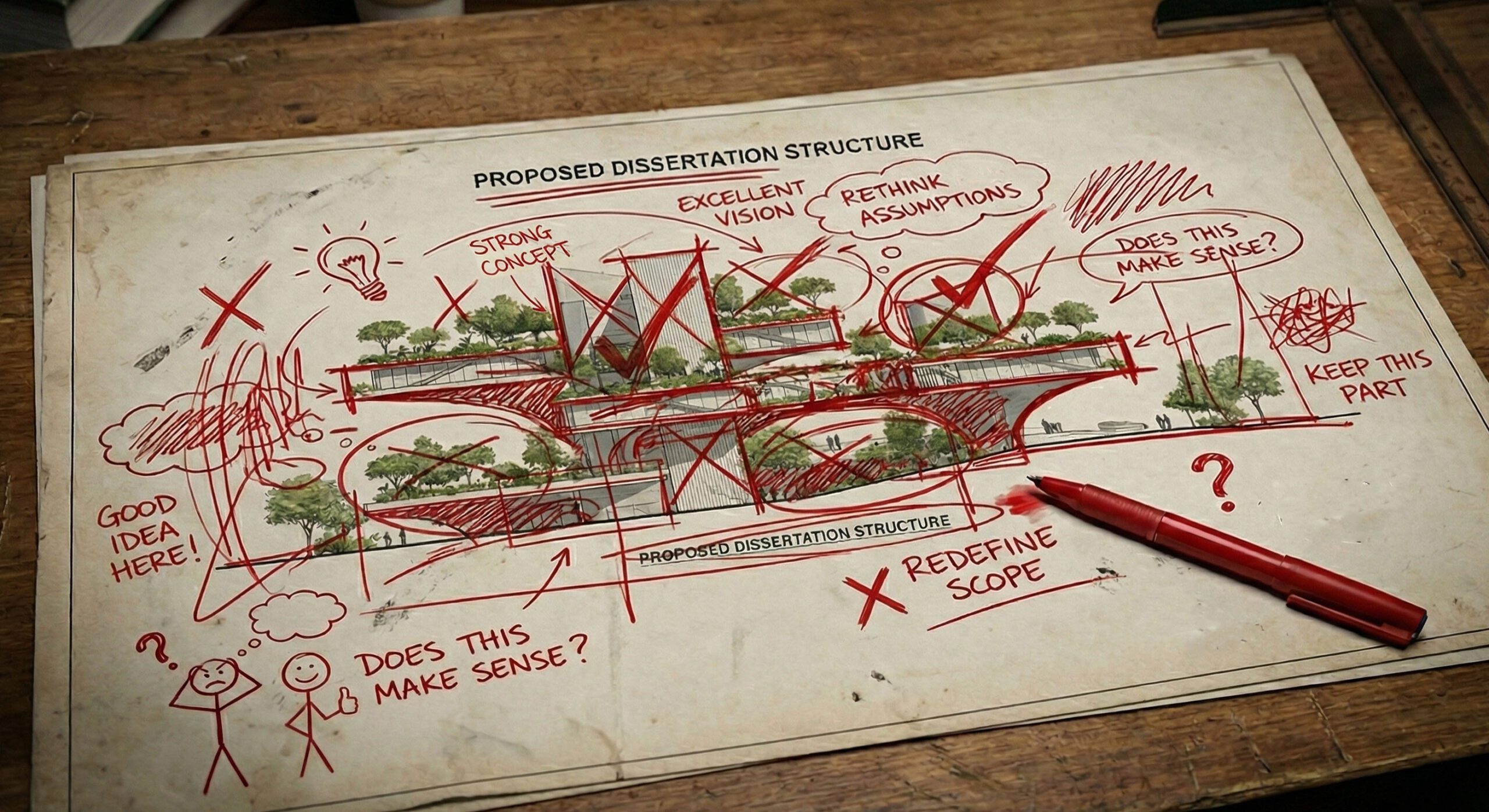

The ideation stage of the design process is inherently messy; for clarity, the findings are distilled and presented in a logical sequence.

Functional Decomposition

Analyzing the problem “how can we make the learning that occurs while writing an essay visible?” in further depth reveals two interconnected and sequential functions:

- Capturing the Process (tracking data of the writing activity)

Flower & Hayes (1981) outline three recursive phases of writing:- Planning (setting goals, generating ideas, organizing information)

- Translating / formulating (writers express their ideas in words and coherent text)

- Reviewing (evaluation and revision of the text)

- Making Sense of It (analyzing and presenting that data in accessible ways)

A solution needs to address both functions and can be a combination of solutions. Most of my ideation centred on Capturing the Process, since the second function, Making Sense of It, depends on it.

Worst Possible Solutions

In considering the worst possible solutions, several important considerations and options for the solution space became apparent. Assessment security often became the primary focus, at the expense of crucial factors such as student agency, psychological safety, increased workload, stress, and disruption (contributing to extraneous cognitive load), and practices that can be easily faked. Ironically, many of these solutions resembled current controversial practices such as TurnItIn and proctoring. Here are a few worst possible solutions:

- Life Recording – a student must record themselves for the entire semester, always.

- Word Count Increment Penalty System – a visible meter tracks the total word count added in 15-minute intervals. If the count drops or stalls for too long, the student receives a penalty.

- Random Prompt Interruption Quiz – writing software interrupts the student every 15-20 minutes with a timed, multiple-choice quiz based on the sources cited so far, requiring perfect recall. Any sentences utilizing sources that the student was unable to answer is automatically removed from the writing.

- Trial by Media – a student’s working document, including all research, source notes, and initial ideas are broadcast live for anyone (e.g., teacher, peers) to see.

Possible Solutions

“There is no end to the number of solutions or approaches to a wicked problem”

(Corbin et al., 2025, p. 8)

The culmination of the ideation, was further elaborated on with both ChatGPT 5 (OpenAI, 2025) and Gemini (Flash 2.5) (Google, 2025) until what felt like a saturation of ideas was reached. To compare and contrast the solutions, key characteristic categories were developed in discussion with LLMs (Google, 2025; OpenAI, 2025). The following table is the result of this work with methods in no particular order.

Table 1 – Comparative Analysis of Process-Based Tracking Methods

| Method | About | Process stage when is the process tracked? | Locus of Visibility what is the source? | Granularity what is the level of detail? | Authenticity how authentic to the task is the tracking method? | Structure how is the tracking method structured? | Effort what is the required effort? |

| Think-Aloud Protocols | Verbalized thinking process during the task | During the task | Internal cognition | Micro | Low | Emergent – Semi-structured | High |

| Pre-writing Activities | Research, brainstorming, or outlining that reveal planning and early ideas | Before the task | External trace | Macro | High | Emergent – Semi-structured | Low-Medium |

| Learning Journals | Collection of thoughts and reflections over time | All stages | Internal cognition expressed as external text | Micro | Low-Medium | Emergent | Medium-High |

| Process Logs / Portfolios | Collections of research, drafts, artifacts, and decision points over time | All stages | External trace | Varies | Medium | Emergent | Medium-High |

| Reflection Activities | Post-task analyses that reveal learning insights | After the task | Internal cognition | Macro | Low-Medium | Emergent – Prescriptive | Medium |

| Self- / Other-Assessment | Evaluations of work-in-progress showing judgment and monitoring | After the task | Internal cognition | Macro | Low-Medium | Emergent – Prescriptive | Low-Medium |

| Goal Setting & Goal-Tracking Artifacts | Documents tracking objectives and progress, showing strategic planning | Before and during the task | Internal cognition externalized | Macro | High | Semi-structured – Structured | Low-Medium |

| Staged Drafts | Sequential drafts showing development and revision decisions over time | During the task | External trace | Macro | High | Structured | Medium |

| Extended Resources | An outline of all the resources used, including texts, people, and GenAI | After the task | External trace | Macro | Low | Semi-structured | Medium |

| Activity History (forum, AI prompt log, etc.) | Automated logs of engagement, edits, and process patterns | During the task | External behavioral trace | Micro-Medium | Integrated (automatic) | Emergent (automatic) | Low (automatic) |

| Keystroke Logging / Screen Recording | Automated digital capture of actions | During the task | External behavioral trace | Micro | Integrated (automatic) | Emergent (automatic) | Low (automatic) |

Idea Selection Criteria

Determining which of the many ideas are most appropriate should be guided by a solid theoretical understanding. Drawing upon a literature review I conducted on Process-Based Writing Assessment (Granchelli, 2025), key themes emerged.

Assessment

Assessment is a key reason of why we are making the writing process visible and can be better understood categorized as:

- Assessment of learning (summative)

- Assessment for learning (formative)

- Assessment as learning (self-assessment or assessing others)

(Efendi & Festiyed, 2019)

This is a helpful framework, but in reality, assessment often addresses multiple, if not all these goals (Efendi & Festiyed, 2019).

Although the assessment modality is important, tracking the writing process is not inherent to a single modality. For example, the analysis of keystroke logging can be offered to writers in real-time, supporting assessment for learning, or it can be given to instructors at the end as a means of assessment of learning (Adhikari, 2023).

This factor is not a primary criterion for selecting a method of making the writing process visible but will be beneficial in the further development of the selected concept. I take a student-centred approach that prioritizes maximizing learning resulting in proposed solutions that emphasize assessment for and as learning.

Benefits of Process-Based Assessment

By emphasizing process over product, process-based techniques support writing skills, metacognitive development, and academic integrity. Making the process of writing visible brings further emphasis to the process of writing, encouraging the use of writing for thinking, as opposed to a final product (Welch, 2024; Wingate & Harper, 2021). Additionally, this granular view of the writing process can demystify the steps of writing and how an essay is formed (Welch, 2024). Making learning visible externalizes the underlying thinking, which can foster reflection and critical thinking, leading to metacognitive and self-regulating skills (Bowen et al., 2022; Glasswell & Parr, 2009). Making learning visible can inspire academic integrity by showing learners that “meaningful learning occurs through exploration, experimentation, and reflection, rather than simply aiming for a polished final product” (Gagich, 2025, p. 3). Because the learning process is difficult to fake, tracking it can enhance academic integrity through assessment security; however, as noted earlier in Converging a Wicked Problem: ‘Good Enough’, assessment security should not compromise the learning experience.

Challenges of Process-Based Assessment

Process-based techniques can be problematic by increasing extraneous demands, being overly prescriptive, and requiring extensive time to assess. Extraneous cognitive load can hinder student’s learning if it does not contribute to it (e.g., the active recording process (Wingate & Harper, 2021), or the passive distraction of being watched (Adhikari, 2023)). It can also demotivate students if it is unnatural or perceived as ‘busywork’ (Gagich, 2025). A prescribed process has the danger of stifling creativity, exploration, and fostering a learned dependence on that process (Adhikari, 2023; Barnhisel et al., 2012; Gagich, 2025). The usability of a process is often limited by how well both the process and its resulting data can be understood, affecting both students’ ability to enact it and educators’ ability to evaluate it.

Conclusion

This phase of the Double Diamond design process involved an extensive exploration of the solution space. A range of methods for making the writing process visible were identified, along with key qualities and considerations for their use. This exploration underscored the importance of assessment for and as learning, and further revealed that making learning visible is not simply a matter of tracking output, but of externalizing underlying thinking to support metacognition and self-regulated learning. Ultimately, it is clear that any solution to the question, “how can we make the learning that occurs while writing an essay visible?” will be highly contextual.

Explore the full ideation process on Miro.

References

Adhikari, B. (2023). Thinking beyond Chatbots’ Threat to Education: Visualizations to Elucidate the Writing or Coding Process. Education Sciences, 13(9), 922. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090922

Barnhisel, G., Stoddard, E., & Gorman, J. (2012). Incorporating Process-Based Writing Pedagogy into First-Year Learning Communities: Strategies and Outcomes. The Journal of General Education, 61(4), 461–487. https://doi.org/10.1353/jge.2012.0041

Bowen, N. E. J. A., Thomas, N., & Vandermeulen, N. (2022). Exploring feedback and regulation in online writing classes with keystroke logging. Computers and Composition, 63, 102692. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2022.102692

Corbin, T., Bearman, M., Boud, D., & Dawson, P. (2025). The wicked problem of AI and assessment. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 0(0), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2025.2553340

Efendi, E. & Festiyed. (2019). Preliminary study of authentic assessment that focus on self assessment and portfolio assessment using problem based models in senior high school. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1317(1), 012177. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1317/1/012177

Flower, L., & Hayes, J. R. (1981). A Cognitive Process Theory of Writing. College Composition and Communication, 32(4), 365–387. https://doi.org/10.2307/356600

Gagich, M. (2025). Using Process-Based Pedagogical Assessment Practices to Challenge Generative AI in the Writing Classroom: In P. W. Wachira, X. Liu, & S. Koc (Eds.), Advances in Educational Marketing, Administration, and Leadership (pp. 1–32). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/979-8-3693-6351-5.ch001

Glasswell, K., & Parr, J. M. (2009). Teachable Moments: Linking Assessment and Teaching in Talk around Writings. Language Arts, 86(5), 352–361.

Google. (2025). Gemini (Flash 2.5) [Large language model]. https://gemini.google.com/

Granchelli, A. (2025). Process-Based Writing Assessment: A Literature Review [Student paper]. Department of Curriculum & Instruction, University of Victoria. https://agranchelli.com/process-based-writing-assessment/

OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT 5 [Large language model]. https://chat.openai.com/

Welch, B. (2024). Demystifying Writing: Collaborative Rubrics and Process-Based Feedback. American Association of Philosophy Teachers Studies in Pedagogy, 9, 128–148. https://doi.org/10.5840/aaptstudies202472288

Wingate, U., & Harper, R. (2021). Completing the first assignment: A case study of the writing processes of a successful and an unsuccessful student. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 49, 100948. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2020.100948