The final phase of the Double Diamond design process is to converge the solution space, ultimately to one final solution for the problem. Within the problem space of assessing writing of undergraduate students in a generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) world, the problem to solve is:

“How can we make the learning that occurs while writing an essay visible?”

This was determined by first exploring the problem space, documented in Attempting to Define a Wicked Problem, and then converged upon, in Converging a Wicked Problem: ‘Good Enough’. In Mapping the Solution Space, the solution space was explored to define the following categories of process-based tracking methods:

- Think-Aloud Protocols – Verbalized thinking process during the task

- Pre-writing Activities – Research, brainstorming, or outlining that reveals planning and early ideas

- Learning Journals – Collection of thoughts and reflections over time

- Process Logs / Portfolios – Collection of research, drafts, artifacts, and decision points over time

- Reflection Activities – Post-task analyses that reveal learning insights

- Self- / Other-Assessment – Evaluations of work-in-progress showing judgment and monitoring

- Goal Setting & Goal-Tracking Artifacts – Documents tracking objectives and progress showing strategic planning

- Staged Drafts – Sequential drafts showing development and revision decisions over time

- Extended Resources – An outline of all the resources used, including texts, people, and GenAI

- Activity History (forum, AI prompt log, etc.) – Automated logs of engagement, edits, and process patterns

- Keystroke Logging / Screen Recording – Automated digital capture of actions

The purpose of this final design step is to converge the many ideas into a single idea, and then to fully explore and prototype that idea.

Weighted Decision Matrix

A weighted decision matrix is a methodological process that compares and contrasts ideas against criteria in order to determine the best solution (Ostafichuk et al., 2019).

Through Mapping the Solution Space, several key considerations for making the writing process visible were identified:

- Emphasis on the process of writing

- Metacognitive skill development

- Inspire academic integrity

- Minimal extraneous demands

- Allow sufficient room for play

- Minimal time to understand the data

These factors acted as the starting point for the idea selection criteria. With support from LLMs (Google, 2025; OpenAI, 2025), I refined the criteria, mapped links between the criteria, and winnowed them down, repeatedly ensuring saturation was met in order to land upon the final selection criteria. I then designed a rubric with support of Gemini (Google, 2025), and a literature review I conducted on Process-Based Writing Assessment (Granchelli, 2025). The final step for designing the weighted decision matrix was to assign each criteria a relative weight which was also done in tandem with Gemini (Google, 2025). This process not only culminated in the following selection criteria, Table 1 – Criteria for Evaluating Process-Based Tracking Methods, but was also a great practice for deeply understanding the considerations of process-based tracking.

Note. An important criterion was missed, which is accessibility. The two process-based tracking methods where access can be a significant barrier (Activity History and Keystroke Logging / Screen Recording), already scored poor in the weighted decision matrix without accessibility as a criterion, and were not pursued in this design process.

Table 1 – Criteria for Evaluating Methods of Making the Writing Process Visible

| Criteria | Weight | Rationale for Weighting | Strong Method (High Viability) | Average Method (Moderate Viability) | Weak Method (Low Viability) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimizes Time to Understand the Data (Scalability & Diagnostic Efficiency) | 25% | The Limiting Factor. As Adhikari (2023) notes, if the method takes 4-5x longer to grade (Park, 2002), it is unsustainable regardless of its pedagogical value. This is the “kill switch” criterion. | Efficiency & Actionability: The data immediately visualizes “where the student is” and “where they need to go” (Glasswell & Parr, 2009), bypassing the need for lengthy investigation. Sustainable Scalability: Solves the “limiting factor” (Adhikari, 2023) by organizing process data into digestible patterns, avoiding the “4-5x” workload increase (Park, 2002). | Partial Clarity: The data requires some digging to interpret. It may be visible to the learner, but they struggle to translate the data into specific improvements. | Noise: The data is “noisy” (e.g., raw logs) and takes too long to decode. It is opaque or irrelevant to the learner’s personal growth. |

| Emphasizes the Process of Writing (Recursive Pedagogy & Performance) | 20% | The Goal. This is the core pedagogical objective. If the method emphasizes the product over the process, it fails the fundamental design goal (Wingate & Harper, 2021). | Recursive Nature: Validates the recursive nature of writing (Gagich, 2025). Demands visible investment of time/energy. Process-Targeted Feedback: Feedback targets the process (why/how strategies work) rather than the product (what to fix), enhancing performance and speed (Bowen et al., 2022; Adhikari, 2023). | Process as Checkpoint: Requires drafts, but feedback is product-oriented (fixing the text, not the writer). Linearity: Acknowledges process but treats it as a linear checklist rather than a recursive cycle. | Product-Only: Ignores the journey. Feedback is limited to the final artifact. Invisible Actions: Actions remain invisible, preventing assessment of the strategy involved (Welch, 2024). |

| Inspires Academic Integrity (Authenticity & Security) | 20% | The Context. In a GenAI world, if the method is easily “reverse-engineered” or faked, the validity of the assessment collapses. | Authentic Engagement: Values “exploration and experimentation,” incentivizing the struggle of learning. Process is “difficult to fake” and personal. Intrinsic Security: Granular analysis serves as a natural barrier to AI without excessive surveillance (Adhikari, 2023). | Security via Surveillance: Relies on policing. Makes cheating difficult, but prioritizes assessment security over learning, creating an adversarial dynamic. External Motivation: Students comply out of fear of being caught, not a desire to learn. | Reverse-Engineerable: Requirements are generic and can be generated by AI after the final product is written. Product-Centric: Fails to value “linguistic diversity,” effectively incentivizing AI use for a polished result. |

| Opportunities for Metacognitive Skill Development (Self-Regulation & Empowerment) | 15% | The Outcome. Self-regulation is vital (Bowen et al., 2022), but a method can still be “functional” with lower metacognition if it is secure and efficient. | Externalizes Thinking: Forces students to “externalize underlying thinking.” Reflection is integrated as constant self-assessment. Empowerment: “Demystifies” the journey, building confidence and cultivating a unique writer’s voice (Welch, 2024). | Episodic Reflection: Reflection occurs (e.g., a final reflection paper), but is separated from the active work process. Passive Scaffolding: Scaffolding is present, but students follow it mechanically without developing internal self-regulation tools. | Implicit Process: Assumes students already possess the tools to write. The “how” remains a mystery. No Self-Regulation: No feedback loop exists for the student to assess their own progress during the task. |

| Allows Sufficient Room for Play (Non-Linearity & UDL) | 10% | The Equity. While theoretically vital (CAST, 2024), in a weighted matrix, this often acts as a pass/fail gate rather than a primary driver of the score. | Universal Design: Aligns with UDL by offering “multiple means of action and expression” (CAST, 2024). The method is agnostic to the input (e.g., accepts voice, diagrams, or text). Agency: Validates “busy” or chaotic workflows. Students define their path, avoiding “learned dependence” (Adhikari, 2023). | Accommodation-Dependent: The method works for a standard linear workflow but requires “special exceptions” or accommodations for neurodivergent learners, rather than being inclusive by design. Partial Rigidity: Allows for revision but creates friction for non-standard approaches (e.g., requiring a linear outline even if the student thinks radially). | Construct Irrelevant Barriers: Enforces a “normative” process that actively disadvantages diverse learners (e.g., flagging non-linear editing as “suspicious”). Enforces Conformity: Requires strict adherence to a linear sequence. Students focus on masking their natural process to satisfy the checklist. |

| Minimizes Extraneous Demands (Cognitive Load & Motivation) | 10% | The Usability. High cognitive load (Sweller, 1998) is bad, but students can tolerate some friction if the learning payoff is high. | Seamless Integration: Tracking adds zero extraneous load; the act of documenting is the learning. Motivation: Students engage honestly because they view the tracking as a support tool, not “busywork” (Gagich, 2025). | Manageable Friction: Adds some “active” friction (e.g., saving versions), but does not derail the train of thought. | High Extraneous Load: Actively distracts from learning (e.g., complex protocols) or causes passive stress (e.g., surveillance anxiety) (Sweller, 1998). Busywork: Perceived as administrative, leading to disengagement. |

Selection Process

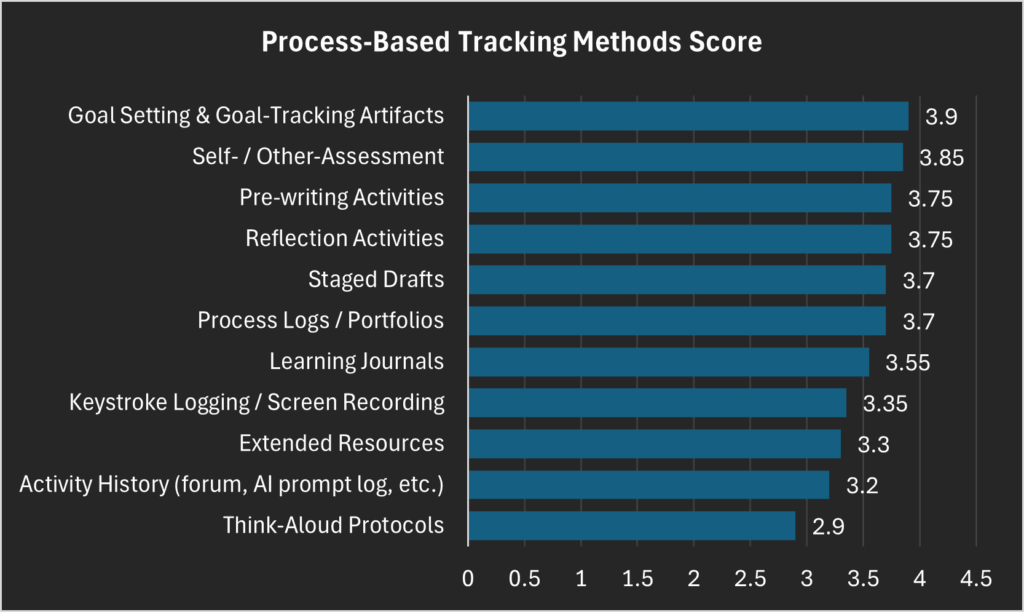

Each process-based tracking method was evaluated against the criteria, while utilizing LLMs to include multiple perspectives. Each method was scored using Gemini Flash 2.5 (Google, 2025) and ChatGPT 5 (OpenAI, 2025), and I then conducted my own assessment, informed by the literature and rationale provided by the LLMs.

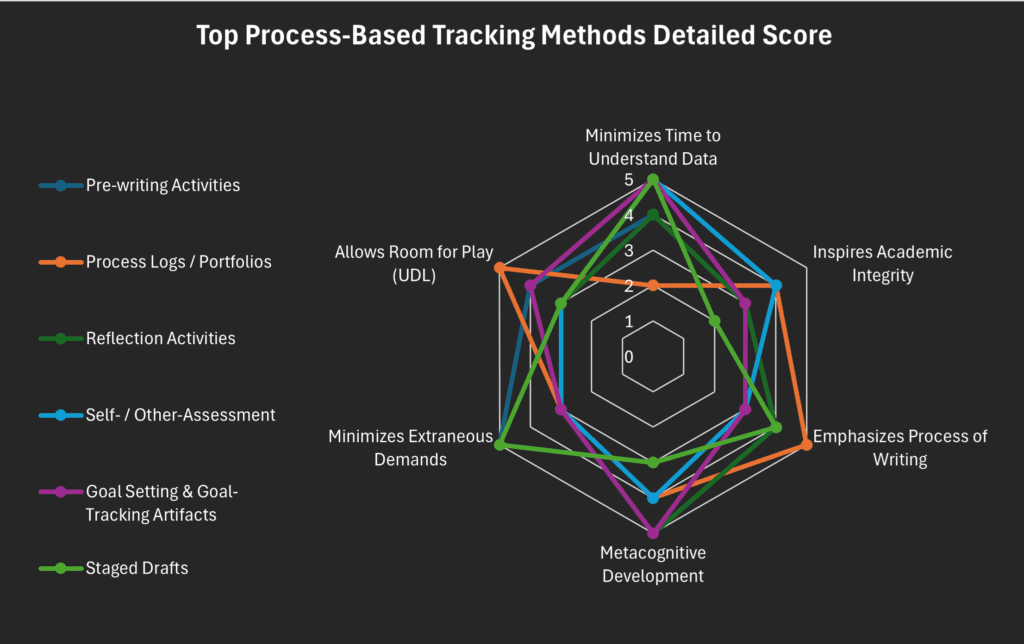

The true value of a weighted decision matrix is the reflective process itself, which fosters a deeper understanding of the problem and its key considerations; the outcome does not necessarily identify the best concept (Ostafichuk et al., 2019). The scores of the top six ideas were remarkably close, which is surprising given how different each individual criterion was scored. The top six concepts are:

- Goal Setting & Goal-Tracking Artifacts – Documents tracking objectives and progress showing strategic planning

- Self- / Other-Assessment – Evaluations of work-in-progress showing judgment and monitoring

- Pre-writing Activities – Research, brainstorming, or outlining that reveals planning and early ideas

- Reflection Activities – Post-task analyses that reveal learning insights

- Staged Drafts – Sequential drafts showing development and revision decisions over time

- Process Logs / Portfolios – Collection of research, drafts, artifacts, and decision points over time

A strong negative correlation emerged between Minimizing Time to Understand Data and Inspiring Academic Integrity. This highlights either a need to reimagine the criteria or reveals an underlying characteristic of process-based tracking methods. When the criteria are compared, this tension becomes clear: data that is messier and/or more abundant is inherently more difficult to interpret, yet it can better support academic integrity by being harder to fake and by placing greater emphasis on process.

A Solution for Making the Learning Visible

There are seemingly endless ways to address the challenge of making the learning that occurs during essay writing visible. The most effective solution depends on the context and may draw upon multiple concepts. When developing a prototype, it was easy to be pulled toward simply scaffolding the essay writing process, which shifts the focus away from the goal of making learning visible. Future iterations of this design process could explore removing ‘essay’ from the problem definition to encourage deeper engagement with writing as an instrument for learning, rather than a focus on the essay as an artifact.

“Complexity is good; it is confusion that is bad”

(Norman, 2013, p. 246)

I explored one process-based tracking method by integrating components of the strongest ideas into an essay writing task. This approach leveraged a granular method for tracking process to inspire academic integrity, along with self-assessment and reflection components to support metacognitive development. If implemented well, these practices can contribute to learning while simultaneously making learning visible. I avoided significantly increasing a student’s workload and an educator’s marking time through careful scaffolding. The goal is to ensure the process-based methods employed feel authentic and are not perceived as busywork (Gagich, 2025); however, if the process is too unstructured, students could complete the task entirely with GenAI (Bauer et al., 2025).

Accessibility and usability are key considerations that allow all students to succeed (CAST, 2024; Choi & Seo, 2024; Norman, 2013). Universal Design for Learning Guidelines is embedded in the essay writing task to ensure there are multiple means of engagement, representation, and action and expression (CAST, 2024) and will be able to function in both a low- and hi-tech environment. The instructions of the essay writing task are crucial signifiers communicating what success is (Norman, 2013).

I explored opportunities that can function with or without the use of GenAI. I intentionally avoided explicitly involving GenAI for the following reasons:

- Accessibility concerns for students, as only those with adequate access and technical skills can use GenAI effectively (Nikolic et al., 2024; Patvardhan et al., 2024)

- Gaps in educator’s technological knowledge (Celik et al., 2022)

- GenAI adoption is inconsistent across educators and institutes

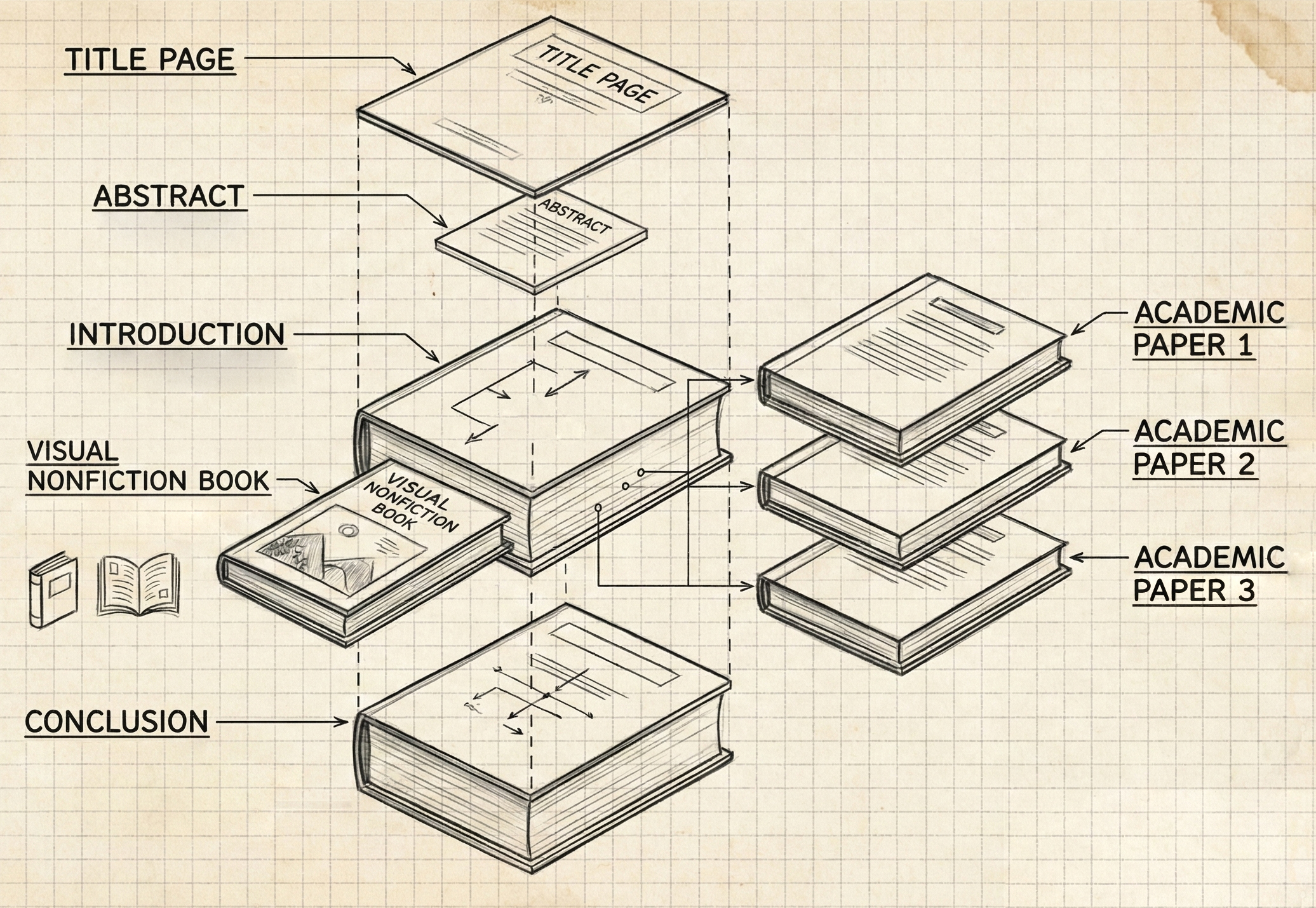

Prototype

The following one-page essay writing task utilizes a variety of process-based tracking methods to make the learning visible that occurs while writing an essay. The development of this prototype underwent thorough iteration:

- The skeleton of the assignment was created based from rough prototypes of process-based tracking methods (pre-writing activities, self-assessment, reflection activities, and aspects of process logs)

- The assignment was further refined with ChatGPT 5 (OpenAI, 2025) and Gemini Flash 2.5 (Google, 2025)

- Four cycles of iterative, simulated empathy mapping and user testing from undergraduate students and teachers of various skill levels

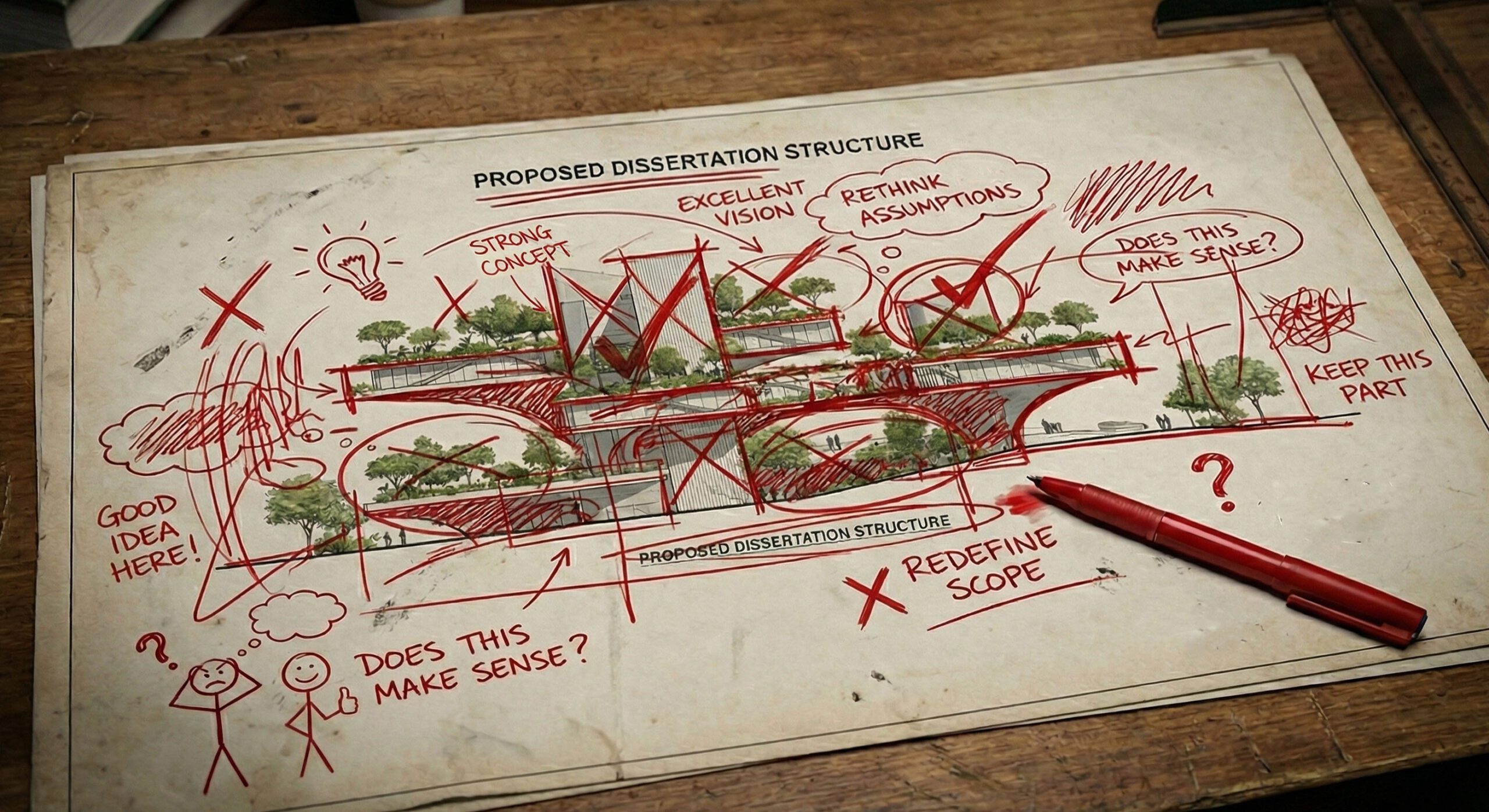

Empathy mapping and user testing were crucial in revealing the perspectives of those who will engage with this design (Nielsen, 1994; Norman, 2013). Some significant pain points were identified such as vocabulary, task confusion, and the need for examples. Incorporating all the feedback was difficult and ultimately, while the essay writing task is authentic, students see some components as busywork or irrelevant. There are inherit limits to the influence a single assignment can have in inspiring students to value the learning process.

Reflection

A post-launch reflection was conducted to analyze the prototype’s successes, challenges, lessons learned, and next steps. I simulated student and instructor feedback of this assignment emphasizing a diversity of expertise and GenAI use (Google, 2025). Naturally, this has limitations, and it is highly recommended to engage with human user testing. The following reflections will reference this user feedback and interweave theoretical underpinnings previously discovered throughout this design process.

Successes

This essay writing task has directly addressed its primary design goal of making the learning that occurs visible. It externalizes Flower and Hayes (1981) recursive writing process of planning, formulating, and reviewing. This scaffolded process especially supports less proficient writers (Wingate & Harper, 2021). Educators and students both shared that learning was evident while viewing the connections made in the Layered Research & Ideas phase and was further evident in the Reflection phase. This also allowed educators to discern where students cognitively offloaded to GenAI. Additionally, guiding the writing process and emphasizing its value encouraged students to focus on their own thinking rather than just the final product. These comments agree with earlier findings that a granularly tracked writing process can lead to academic integrity.

The Blueprint and Layered Research & Ideas phases allowed opportunities to demonstrate high-level thinking independent of proficient writing skills. This offered a more equitable opportunity for learners by supporting multiple means of engagement, representation, and action and expression (CAST, 2024).

This task guided learners through an authentic essay-writing process with a tracking method that supported the process while also scaffolding their thinking from lower- to higher-order cognitive skills.

Challenges

A prescribed process, specifically in the Blueprint and Layered Research & Ideas phases, was found to stifle advanced writers. This is supported in the literature previously discussed (e.g., Adhikari, 2023; Barnhisel et al., 2012; Gagich, 2025).

Instructors noted the extra time needed to grade the assignments, which stemmed more from having four checkpoints than the word count. This is also extensively represented in the literature and deemed to be the limiting factor to process-based assessment methods (Adhikari, 2023; Barnhisel et al., 2012; Bowen et al., 2022; Maya & Wolf, 2024; Park, 2003; Welch, 2024).

Lessons Learned

The Layered Research & Ideas phase introduced messiness as an artifact of learning and as expected, this messiness was difficult to fake, contributing to assessment security. However, students struggled with this task, as it was often a new way of representing ideas, they were uncomfortable with imperfections, and they experienced uncertainty about expectations.

Metacognitive activities, such as the Reflection and Self-Assessment, acted as a great lens for verifying learning, as instructors easily identified when students relied primarily on GenAI. When students had full freedom to use GenAI in their writing task, the final essay proved to demonstrate the least variance between students.

Next Steps

There are several recommended steps in the continued development of this learning task. First and foremost, this assignment should be tested in an undergraduate classroom, with data collected through analysis of completed assignments as well as feedback from both students and instructors. In the meantime, the identified pain points can be addressed: time to assess, addressing the prescribed process, teaching how to be messy, and AI literacy.

The extra time that process-based methods demand is an ongoing struggle. This assignment can explore offering automated or complete/incomplete grading for some of the phases. Conversely, a short assessment and correction early in the writing process (e.g., the Blueprint) can have immense impacts on the final product.

For more proficient writers, the prescribed process posed a barrier to creativity and exploration. Allowing for a self-designed writing process could ensure that process steps are recorded while still offering freedom. However, as Welch (2024) found, this can quickly increase the burden on instructor workload.

A ‘messy’ artifact proved to be a pain point. It is an ambiguous term that can be more clearly defined, and students were not comfortable with submitting something messy. Potentially reframing this artifact into a concept map or flowchart would be better. Conversely, this may be useful learning in itself; Corbin, Walton, et al. (2025) share that nearly every educational task recruits calculative thinking, “a focus on efficiency and utility” (p. 6), as opposed to meditative thinking, where one “remains open to what is not yet known” (p. 6). This discomfort students have with the unknown may be a symptom of a deeper problem that should be supported as a learning outcome than avoided with design.

AI literacy yet again emerged as a core pain point even though it is not intrinsic to this essay writing task. Its appropriate use, including what is permitted and prohibited, should be clearly articulated. When GenAI use is allowed, it should be explicitly included as a learning outcome, otherwise only students with prior technical skills are likely to benefit (Nikolic et al., 2024; Patvardhan et al., 2024).

Finally, the essay format itself should be reconsidered. As it was part of the problem statement, it became a significant focus of the solution. The essay has a historical and lasting influence as an instrument to assess students learning, even though it has drifted far from its original roots (Corbin, Walton, et al., 2025). The essay format is rigid and does not provide multiple means for representation nor action and expression, contrary to Universal Design for Learning Guidelines (CAST, 2024).

Conclusion

Engaging sincerely with the design process requires a substantial amount of work, and GenAI has redefined what is possible, offering significantly more opportunities for deep learning (Bauer et al., 2025). The design process and the role of GenAI is explored in greater depth within this post: A GenAI Enhanced Design Process: Exploring Affordances and Limitations.

In this project, I explored the problem space of assessing writing of undergraduate students in a GenAI world and narrowed the focus to: how can we make the learning that occurs while writing an essay visible? The result is a simple, no-tech undergraduate essay-writing task that may not reflect all the effort behind it; yet engaging deeply with this problem space provided the confidence to support this solution, along with the humility to recognize that it is not necessarily the best, and certainly not the only, solution. This problem is wicked and, by definition, offers no signal when it is solved nor can it even be conclusively solved (Corbin, Bearman, et al., 2025). Therefore, while this outcome is good enough, it should be continuously iterated upon; the design is not finished. This lens of prototype should be extended across the educational field and practice, as the context is constantly evolving and demands ongoing redesign.

Ultimately, the artifact from this process can be viewed as a simple stepping stone to better understand this problem space, and through this human-centred design process, it has become clear just how wicked a problem it is.

Explore the full selection and iterative design process on Miro.

References

Adhikari, B. (2023). Thinking beyond Chatbots’ Threat to Education: Visualizations to Elucidate the Writing or Coding Process. Education Sciences, 13(9), 922. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090922

Barnhisel, G., Stoddard, E., & Gorman, J. (2012). Incorporating Process-Based Writing Pedagogy into First-Year Learning Communities: Strategies and Outcomes. The Journal of General Education, 61(4), 461–487. https://doi.org/10.1353/jge.2012.0041

Bauer, E., Greiff, S., Graesser, A. C., Scheiter, K., & Sailer, M. (2025). Looking Beyond the Hype: Understanding the Effects of AI on Learning. Educational Psychology Review, 37(2), 45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-025-10020-8

Bowen, N. E. J. A., Thomas, N., & Vandermeulen, N. (2022). Exploring feedback and regulation in online writing classes with keystroke logging. Computers and Composition, 63, 102692. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2022.102692

CAST. (2024). Universal Design for Learning Guidelines version 3.0. https://udlguidelines.cast.org

Celik, I., Dindar, M., Muukkonen, H., & Järvelä, S. (2022). The Promises and Challenges of Artificial Intelligence for Teachers: A Systematic Review of Research. TechTrends, 66(4), 616–630. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-022-00715-y

Choi, G. W., & Seo, J. (2024). Accessibility, Usability, and Universal Design for Learning: Discussion of Three Key LX/UX Elements for Inclusive Learning Design. TechTrends, 68(5), 936–945. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-024-00987-6

Corbin, T., Bearman, M., Boud, D., & Dawson, P. (2025). The wicked problem of AI and assessment. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 0(0), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2025.2553340

Corbin, T., Walton, J., Banister, P., & Deranty, J.-P. (2025). On the essay in a time of GenAI. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 0(0), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2025.2572802

Flower, L., & Hayes, J. R. (1981). A Cognitive Process Theory of Writing. College Composition and Communication, 32(4), 365–387. https://doi.org/10.2307/356600

Gagich, M. (2025). Using Process-Based Pedagogical Assessment Practices to Challenge Generative AI in the Writing Classroom: In P. W. Wachira, X. Liu, & S. Koc (Eds.), Advances in Educational Marketing, Administration, and Leadership (pp. 1–32). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/979-8-3693-6351-5.ch001

Glasswell, K., & Parr, J. M. (2009). Teachable Moments: Linking Assessment and Teaching in Talk around Writings. Language Arts, 86(5), 352–361.

Google. (2025). Gemini (Flash 2.5) [Large language model]. https://gemini.google.com/

Larsson, K. (2021). Using Essay Responses as a Basis for Teaching Critical Thinking – a Variation Theory Approach. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 65(1), 21–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2019.1650824

Maya, F., & Wolf, K. D. (2024). An Architecture for Formative Assessment Analytics of Multimodal Artefacts in ePortfolios Supported by Artificial Intelligence. In M. Sahin & D. Ifenthaler (Eds.), Assessment Analytics in Education (pp. 293–312). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-56365-2_15

Nielsen, J. (1994). Enhancing the explanatory power of usability heuristics. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 152–158. https://doi.org/10.1145/191666.191729

Nikolic, S., Sandison, C., Haque, R., Daniel, S., Grundy, S., Belkina, M., Lyden, S., Hassan, G. M., & Neal, P. (2024). ChatGPT, Copilot, Gemini, SciSpace and Wolfram versus higher education assessments: An updated multi-institutional study of the academic integrity impacts of Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) on assessment, teaching and learning in engineering. Australasian Journal of Engineering Education, 29(2), 126–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/22054952.2024.2372154

Norman, D. A. (2013). The design of everyday things (Revised and expanded ed). Basic Books.

OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT 5.1 [Large language model]. https://chat.openai.com/

Ostafichuk, P., Hodgson, A., & Fengler, M. (2019). The engineering design process: An introduction for mechanical engineers (Third edition). Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of British Columbia.

Park, C. (2003). Engaging Students in the Learning Process: The learning journal. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 27(2), 183–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098260305675

Patvardhan, N., Ranade, M., Vandana, & Khatwani, R. (2024). Examining the accessibility of ChatGPT for competency-based personalised learning for specially-abled people. The International Journal of Information and Learning Technology, 41(5), 539–555. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJILT-04-2024-0066

Sweller, J., van Merrienboer, J. J. G., & Paas, F. G. W. C. (1998). Cognitive Architecture and Instructional Design. Educational Psychology Review, 10(3), 251–296.

Welch, B. (2024). Demystifying Writing: Collaborative Rubrics and Process-Based Feedback. American Association of Philosophy Teachers Studies in Pedagogy, 9, 128–148. https://doi.org/10.5840/aaptstudies202472288

Wingate, U., & Harper, R. (2021). Completing the first assignment: A case study of the writing processes of a successful and an unsuccessful student. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 49, 100948. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2020.100948