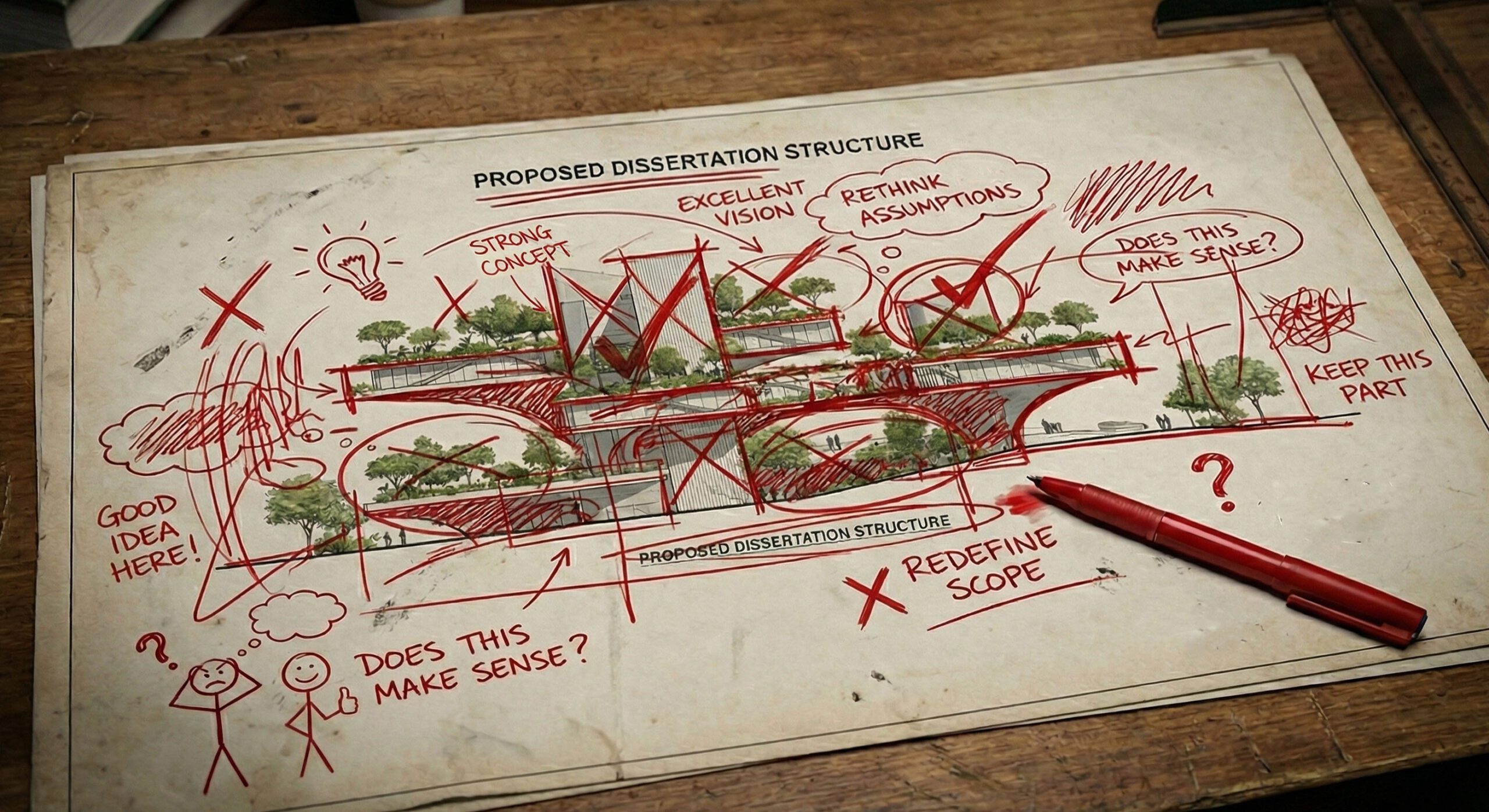

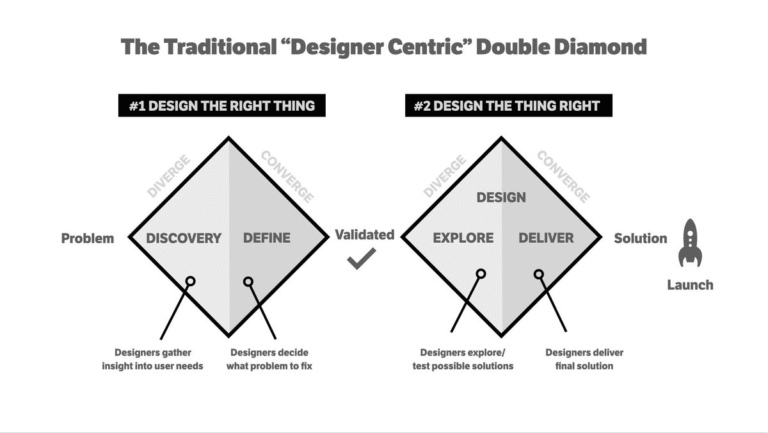

Good designers need to engage in many perspectives, oftentimes simultaneously. That is, the ability to move fluidly between different frames of mind throughout the process, from managerial to focused and from divergent to convergent. Additionally, strong and confident design emerges from the ability to integrate and leverage external support and diverse perspectives—to see things how others do. Generative artificial intelligence (GenAI), particularly large language models (LLMs), holds immense potential within the design process, but it must be used with great care to ensure it supports rather than hinders design. To guide our discussion of the design process, this post will use the double-diamond approach as a framing model, which highlights the need to spend time on both understanding the problem and shaping the solution, each moving from divergent to convergent thinking.

Engaging in a human-centred design approach continues to underscore several important ideas. First and foremost is the need to genuinely keep humans at the centre, especially in education, where learners should always be the primary focus. This may not seem revolutionary, yet much of what is designed offers such a poor user experience.

“Good design starts with an understanding of psychology and technology. Good design requires good communication, especially from machine to person, indicating what actions are possible, what is happening, and what is about to happen.”

(Norman, 2013, p. 8)

Find the Actual Problem

“One of my rules … is simple: never solve the problem I am asked to solve. Why such a counterintuitive rule? Because, invariably, the problem I am asked to solve is not the real, fundamental, root problem.”

(Norman, 2013, p. 217)

The very first step, often missed is finding the right problem to solve—people seem so eager to jump to a solution that they solve the wrong problem (Schön, 2013). Norman (2013) encourages designers to find the source of the problem, instead of just a symptom (Norman, 2013). There’s a fantastic example by Henry Ford (though it’s actually unclear whether he said such a thing): “If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.” If the problem statement were to be ‘faster horses’, one could never reach the solution of cars. It’s only when we truly get to the bottom of the problem, in this case ‘better transportation’, can revolutionary solutions be found.

Where this becomes challenging, or even impossible, is when there is no singular problem, such as in the case of ‘wicked’ problems. A ‘wicked’ problem can be described as just a symptom of another problem, leading to cyclical problem definitions (Corbin et al., 2025). Here, a designer has a lot of work to select which problem is the best starting point, and ultimately, the solution will simply be ‘good enough’.

Variety of Perspectives

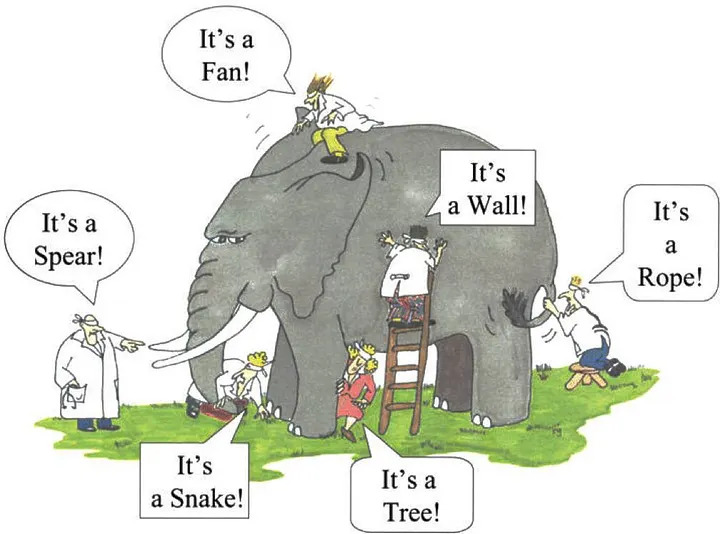

One of my favourite examples is the parable of the blind individuals and an elephant, which clearly exemplifies the need for multiple perspectives. This ability to be open and to engage with a multitude of ideas, at times conflicting, has rippling effects across the entire design process resulting in a better final design.

“If all the viewpoints and requirements can be understood by all participants, it is often possible to think of creative solutions that satisfy most of the issues. Note that working with these teams is also a challenge. Everyone speaks a different technical language. Each discipline thinks it is the most important part of the process. Quite often, each discipline thinks the others are stupid, that they are making inane requests. It takes a skilled product manager to create mutual understanding and respect.”

(Norman, 2013, p. 239)

So how can we incorporate multiple perspectives? Engagement with peers or LLMs is essential, as integrating external perspectives into the design process builds confidence and ensures all aspects are considered. Better still, is to structure these engagements with practices and exercises that encourage new modes of thinking. Such approaches are useful throughout the entire design process, from defining the problem to testing solutions, by guiding thinking in the specific way each phase requires. Here is just a quick list of practices that I have found helpful though my design process:

- Empathy Mapping – considering what various stakeholders say, think, does, or feels

- Research Divergence – consulting the literature

- Problem Mapping – Outlining the interrelation of problems

- Reframing – reconsidering the problem from a different audience

- Five Whys – asking why to a problem, uncovering deeper issues

- Functional Decomposition – deconstructing the problem into single parts

The Role of GenAI

Generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) can play a role at every step of the design process. In fact, it can even do the entire design, though the result will likely be poor with little if any confidence in its quality. The power of GenAI comes with keeping a human-in-the-loop, better still is if the GenAI is transparent with how it reaches its conclusions (Wang et al., 2019). Using GenAI shifts the designer’s role into a managerial one, where considerations are placed in setting the direction for the GenAI to explore, evaluating its output, and correcting where it has strayed.

I found incredible promise with how large language models (LLMs) helped with brainstorming, categorizing, and in general adding breadth to ideas. They are powerful tools for immediate feedback and exploration of an idea. Even if at times it does not add anything new, it demands engagement, and that extra time spent with an idea gives space for the original idea to evolve or new ones to emerge. Even when LLMs are demonstrably incorrect, their errors can still spark new ideas and also require thoughtful effort to correct. For rote tasks, it is so nice to delegate it to a machine. That said, using GenAI effectively requires skill, subject-matter expertise, and critical awareness to recognize when it is incorrect or when cognitive offloading becomes detrimental.

The affordances of LLMs are complex: while they can perform tasks at a surface level, closer examination reveals subtle and significant cognitive implications. First and foremost, there is significant desire to delegate a task to LLMs because they can in fact do the work, but without subject-matter expertise nor personally engaging in the process, then one cannot assess the quality of the solution. Here is just a short list of the potential issues with LLM outputs:

- Bland and generic: content that is rote, obvious, unoriginal, or driven by popularity rather than substance

- Appeasing and placating: emphasizing affirmation of the user rather than the quality or rigor of the content

- Unrealistic: content that is not grounded in reality and is overly optimistic or idealized

- Biased: content that reflects a narrow, often white, Eurocentric perspective

- Hallucinations: content that is factually incorrect or fabricated

This is a lot to navigate, and even with the best intentions, LLMs can have influence on ones thoughts. It can add chaos and extraneous cognitive demands to thinking, derailing individual thought. Additionally, its output could produce an anchoring effect, where users remain closely aligned with the initially proposed solution (Wang et al., 2019). A GenAI partnership also challenges the notion of authorship (though this may prove to have immense benefits because 1. it brings to the forefront that nothing is ‘new’ just rearranged and 2. it may remove the human’s ego from the idea, allowing a more critical perspective). Put simply, is the human-GenAI partnership, GenAI under human control or human under GenAI control (Yang et al., 2021)?

What GenAI is intrinsically missing is the human experience. This, however, is not so unique to GenAI, because each individual human has their own experience and biases. Relying solely on one human, as the empathetic lens, can be just as much a fallacy, since we know that one-size-does-not-fit-all (Norman, 2013). When using GenAI, it’s up to the designer to embed the human element, the emotional nuance, and the lived experience, preferably by involving diverse human perspectives.

Throughout this engagement with GenAI, a user who employs good practices, remains vigilant and corrects GenAI when it is wrong. This process does more than keep the AI in check; it affords users to look inwards, often holding up a mirror that reveals one’s own views and assumptions. For example, the process of challenging GenAI’s biases is inextricably linked to the interrogation of our own. So, in shaping AI to work as we intend, we simultaneously confront our own understanding.

As GenAI is an emerging technology, its responsible and ethical use are still evolving. Knowing when to use and when to avoid GenAI remains a challenge. In many cases, using it properly, by verifying its outputs, can add nothing new and take longer than completing the task independently. Navigating GenAI is complex but increasingly necessary as these technologies continue to demonstrate value across a wide range of contexts, making GenAI literacy a crucial emerging skill for the future.

It the context of design, I consider GenAI akin to another human collaborator. It offers the potential to provide numerous additional perspectives, contributing to the design at every stage of the process. In other words, it gives the designer a new lens to see the world.

References

Corbin, T., Bearman, M., Boud, D., & Dawson, P. (2025). The wicked problem of AI and assessment. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 0(0), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2025.2553340

Google. (2025). Gemini (Flash 2.5) [Large language model]. https://gemini.google.com/

Norman, D. A. (2013). The design of everyday things (Revised and expanded ed). Basic Books.

Schön, D. A. (2013). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Ashgate.

Wang, D., Yang, Q., Abdul, A., & Lim, B. Y. (2019). Designing Theory-Driven User-Centric Explainable AI. Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1145/3290605.3300831

Yang, S. J. H., Ogata, H., Matsui, T., & Chen, N.-S. (2021). Human-centered artificial intelligence in education: Seeing the invisible through the visible. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 2, 100008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2021.100008

Prompt Sequence

Image Generation Prompt Chaining:

- Image text prompt creation and iteration: Gemini 2.5 Flash (Google, 2025)

- Text-to-image creation and iteration: Gemini Nano Banana Pro (Google, 2025)

Initial prompt:

help me work on an image prompt.

I want to make a photo of an individual wearing / trying on a large number of different and eccentric hats. The metaphor that this image should convey is that designers need to engage in a multitude of different thinking from managerial to focused and divergent to convergent.

Note. I shifted the metaphor from hats to glasses after the initial prompt.

Final prompt:

A highly conceptual, photorealistic studio portrait, close-up of a single individual only, with one head and one body, actively trying on wildly eccentric and vibrantly colorful glasses. The figure’s expression conveys playful, deep engagement and exploratory curiosity. Each active pair of glasses distinctly represents a mode of thought: structured, architectural frames with sharp, geometric lines (managerial); whimsical frames with flowing, intricate forms and luminous, swirling colors (divergent); tightly focused, minimal frames in a deep, saturated hue (convergent); frames with elements visually bursting forth with illustrative, brightly colored ideas and sketches (brainstorming); and classic scholar’s spectacles with traditional academic details, featuring rich, vibrant purples or blues (expertise). The setting is an immersive, dramatic interior of a grand, labyrinthine eyewear shop, styled to evoke the magical, wood-paneled, cluttered ambiance of the Ollivander’s wand shop from Harry Potter. Big window in the back. The background is a dense, floor-to-ceiling display of thousands of equally eccentric, vibrantly colored spectacles, creating a fantastical and rich visual tapestry that highlights the subject. Highly dramatic studio lighting, deep shadow and highlight contrast (chiaroscuro) with fantastical color accents. The glasses must look physically realistic, no floating. No text, no words, no logos. The image should be square

GenAI Text-to-Image Bias?

I iterated through a multitude of images and was happy to see a variety of individuals generated including ones that resembled women and Asian ethnicity. It was, unfortunately, predominately generating a white male, and in all the images generated it didn’t hit on the a full representation of humanity, but at least there is the start of diversity with the image generation.