Using the Double Diamond design process, I began exploring the problem space of assessing undergraduate writing in a generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) context. I examined the literature and conducted simulated stakeholder interviews to understand the extent and nuance of the challenge. You can view the whole journey here: Attempting to Define a Wicked Problem. This revealed an interconnected web of problems and symptoms, making it difficult to distinguish causes from effects and underscoring the wicked nature of the problem space.

“Wicked problems can always be described as the symptom of other problems”

(Corbin et al., 2025, p. 9)

Once a problem space has been better understood, the next phase of the Double Diamond design process is to define the singular problem to solve.

“When we set the problem, we select what we will treat as the “things” of the situation, we set the boundaries of our attention to it, and we impose upon it a coherence which allows us to say what is wrong and in what directions the situation needs to be changed. Problem setting is a process in which, interactively, we name the things to which we will attend and frame the context in which we will attend to them.”

(Schön, 2013, p. 40)

The problem definition is key as it dictates what possible solutions may arise. “The way a wicked problem is described determines its possible solutions … In other words, how we frame the AI and assessment challenge predetermines which solutions appear reasonable and which remain invisible” (Corbin et al., 2025, p. 10).

However, in the very nature of a wicked problem, this is impossible, as “[wicked problems] cannot be clearly or conclusively defined.” (Corbin et al., 2025, p. 5). In attempting to converge the problem, I moved forward and backwards again, and still only progressed with a problem that is narrow and incomplete for the whole problem space. Nevertheless, iteration is expected in design, as is settling on “good enough” with a wicked problem (Corbin et al., 2025).

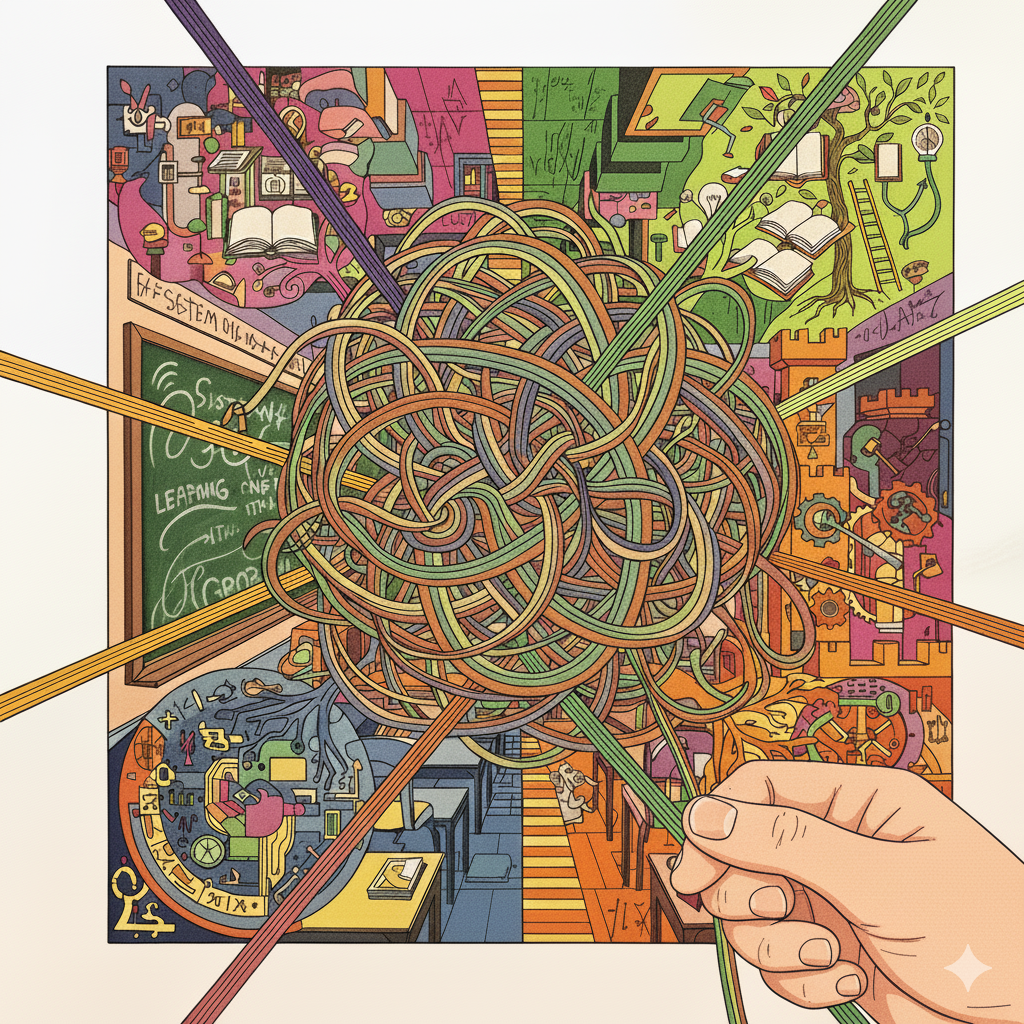

Metaphorically, this problem space is a tangled ball of yarn. I began by attempting to understand various knots and loose strands, and now I must choose a location to start my efforts of untangling it; though every time I would pull at a strand, it became increasingly evident how every other aspect is influenced. I would begin exploring but stop because it did not feel as if I was going to get anywhere. I was stuck in a divergent frame of mind, unable to settle in a direction. Even through various convergent activities, discussions with peers, friends, and large language models (LLMs), I could not make headway. The problem space felt so immense and defining the right question felt so important to get right, not just for this design task but also in its implications for the future of my research.

“Getting the specification of the thing to be defined is one of the most difficult parts of the design, so much so that the [Human-Centred design] principle is to avoid specifying the problem as long as possible but instead to iterate upon repeated approximations.”

(Norman, 2013, p. 9)

Narrowing Activities

Affinity Mapping

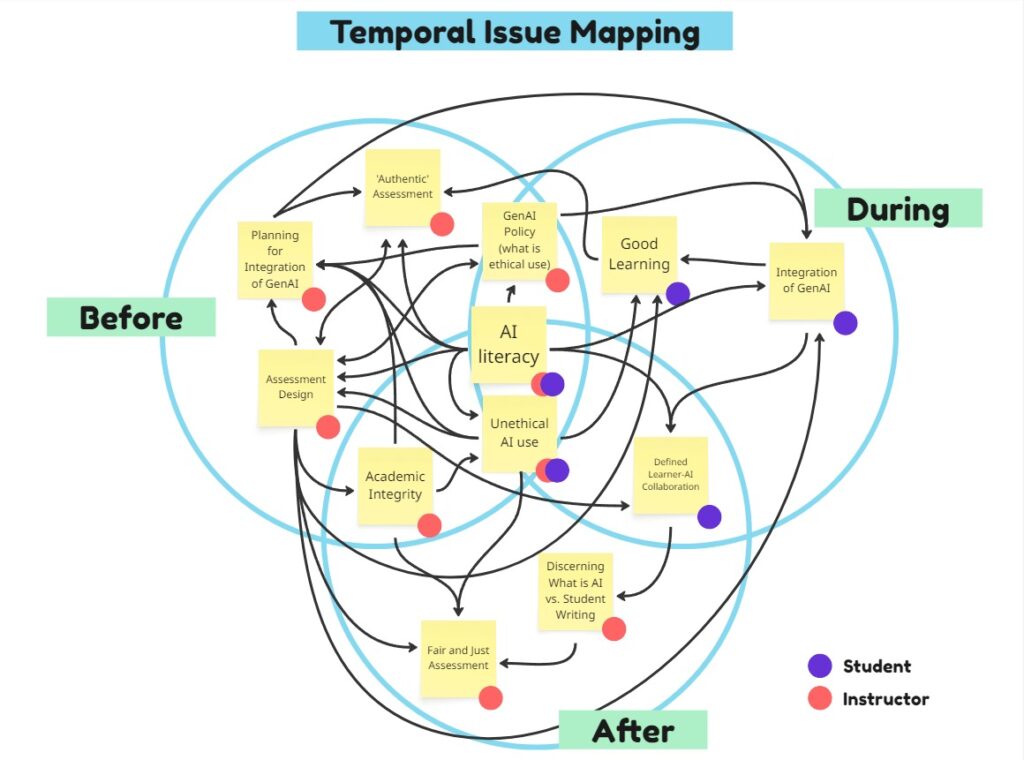

I engaged in issue mapping to understand the problem which pointed to its interconnected nature. Clearly, no single problem emerged, but some issues acted as clear focal points such as: AI literacy, assessment design, and planning for integration of GenAI. See Attempting to Define a Wicked Problem for the two other mappings categorized by stakeholder (student, instructor) and systemic level (Micro, Meso, Macro).

Mapping Issues of Assessing Writing Categorized Temporally: Before, During, and After the Assessment

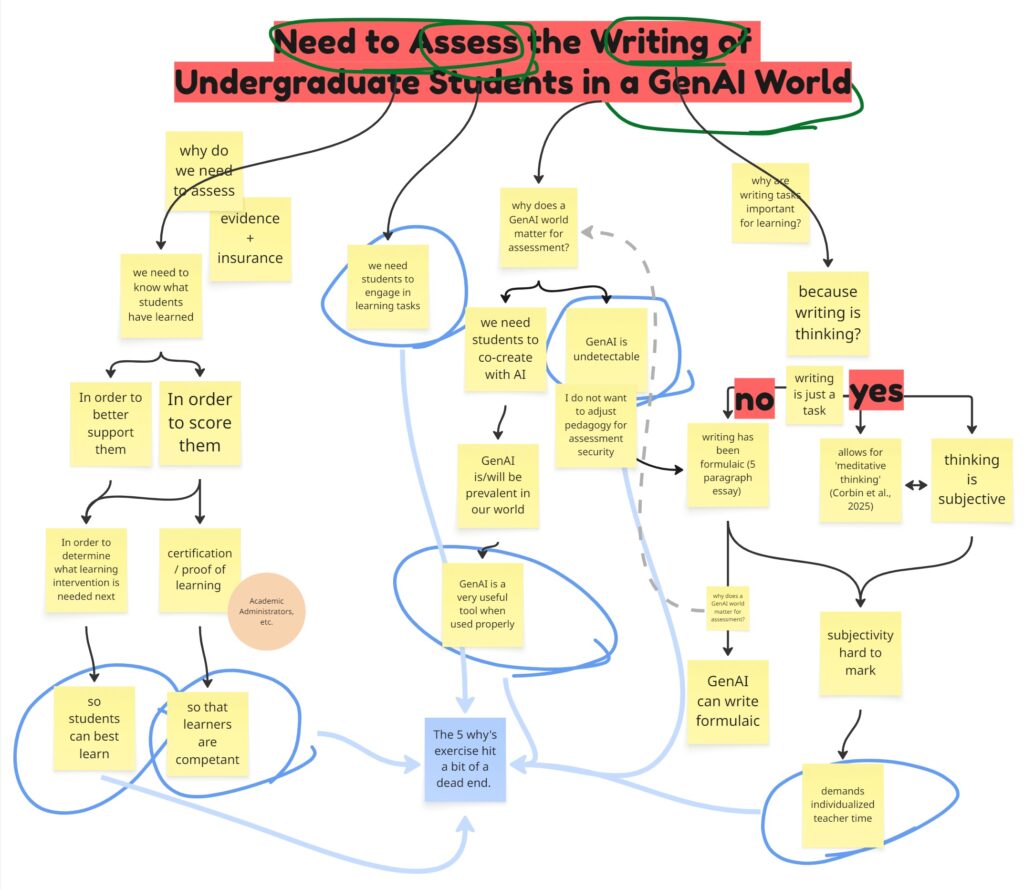

Five Whys

The five ways is an interrogative technique to help understand the root cause of a problem. It consists of asking why a problem exists, recursively, or over and over again. This did not act as a useful technique with this problem space, as the first why could take so many different directions with a focus on assessment, writing, and/or GenAI. In fact, I built up something that looked more like a tree with a variety of branches, than a linear progression of whys. The identified “roots” of the issues did not feel like the true underlying causes; instead, they pointed to existential or narrowly focused questions:

- How can students best learn?

- How can educators assure competency?

- How can GenAI be used properly for education?

- How can we detect GenAI use?

- How can educators provide more individualized support?

Reframing

I engaged in a reframing exercise to shift the perspective of the problem (Dorst, 2011). One reframing dimensions explored was by user:

Students need/want:

- Authentic assessments

- To learn

- To be credentialed

- To prove authorship

So they may ask:

“How can we use GenAI tools to learn/complete the task?”

Teachers need/want:

- To manage validity

- Time-efficient practices

- To understand GenAI

So they may ask:

“How can we fairly and efficiently assess students when GenAI is accessible/utilized?”

Administrators need/want:

- To maintain credibility

- To meet certification standards

- Quantifiable grades

So they may ask:

“How can we uphold academic integrity when GenAI is used by students?”

Discussion

The ability to view new perspectives offered by others, as well as LLMs, proved invaluable to the process. Discussions are a melting pot of ideas, where they can be explored, challenged, and pushed forward in a manner that is fun, connecting, immediate, and motivating. This knowledge sharing is one of few opportunities where personal blind spots can be illuminated.

Cultivating such an environment is incredibly tough, and I feel very grateful for the relationship and community of inquiry that has formed within my project group.

This process is incredibly hard to track. What conclusively came from discussions were instrumental articles, possible ideas, and confidence in the work I was doing.

Picking a Direction

Nothing felt as though the problem was adequately converging; the problem space remained too broad, and no attempt felt appropriately defined or like a worthwhile direction to pursue. Through this process, four some key themes emerged:

- Assessment reliability and validity

- Student learning and competency

- AI literacy

- Academic integrity

I settled on a problem statement that addresses theses emergent themes, is situated in the present, and is agile for the future where human-AI partnerships are may become the norm (Eaton, 2023a).:

“How can we assess learning that has occurred when a task was conducted as a human-AI partnership?”

Ideation

Guided by this problem statement, I began brainstorming and quickly generated numerous solutions, but many felt like they addressed only a subset of the problem, or even a different problem entirely from the one I had initially set out to solve. These ideas clustered in a breadth of topics such as:

- AI detection

- Surveillance

- Penalization

- Process-based methodologies

- Inspiring academic integrity

This solutions space revealed that the problem statement was not well constrained. With such variety, it was hard to dive deeper into a more creative space. I turned to understanding my ideas and analyzing my problem statement.

Assessment security emerged as a property of three of the clusters (AI detection, surveillance, and penalization). It is an important consideration but not a main concern; in fact, Eaton (2023b), warns about focusing on assessment security and how it is different than academic integrity. Designing for assessment security is designing for the few students who engage in academic misconduct, a vast minority of students. Oftentimes, designing for a smaller subset of individuals or for specific needs improves usability for all. This is a concept in Universal Design for Learning (Choi & Seo, 2024) and Human-Centred Design (Norman, 2013). However, in this case, it does not apply to the problem in question: “How can we assess learning that has occurred when a task was conducted as a human-AI partnership?” since assessment security is not the only need. While it is true that focusing on the few students that may cheat will result in a final product that will minimize cheating opportunities for all students, assessment security is a factor that must be balanced against other needs such as developing an authentic and meaningful experience for all students. We do not need assessment that is secure with learning as an afterthought; assessment design should not be dictated by the few that abuse the system. Creating a meaningful learning experience should be our primary goal.

In the end, this phase of ideating solutions revealed that my problem definition needed refinement. It was too unconstrained, resulting in an overly diverse range of solutions (Ostafichuk et al., 2019).

Refining the Problem Statement

Exploring the problem space through ideation uncovered several possible solution directions, and after removing concerns about assessment security, helped define two clear target:

- Process-based methodologies

- Inspiring academic integrity

These goals continue to address the four themes (assessment reliability and validity, student learning and competency, AI literacy, academic integrity), that emerged in the first round of problem definition.

“AI-resistant assessments promote students’ ownership of their learning journey through the documentation of their processes and critical reflection regarding their decisions. This focus on the learning process over the final product ensures students build critical, adaptable skills while engaging deeply with the material”

(Khlaif et al., 2025, p. 3)

As I continued exploring the problem space through research, one theme became increasingly clear: making learning visible. In hindsight, this is fundamental, since educators cannot assess what they cannot see (Welch, 2024). Sabbaghan (2025) states “academic integrity will be about making learning visible as much as possible” (26:00). Assessment can also draw upon insights from Human-Centred Design where visibility is a core feature that highlights signifiers and affordances (Norman, 2013). Human-Centred Design offers two key angles depending on who the primary subject is. For the educator, visibility of the learning process is a necessity for process-based assessment and from the learner’s perspective, another layer emerges: visibility not only supports understanding of the process but also reveals the mechanics of assessment, enabling learners to engage in self-assessment.

“How can we make the learning that occurs while writing an essay visible?”

Converging the problem space from “assessing writing of undergraduate students in a GenAI world” to this final problem was clearly a non-linear approach. This is not the singular problem of this problem space—it cannot be, as it is a wicked problem. It “cannot be clearly or conclusively defined” (Corbin et al., 2025, p. 5), it is simply ‘good enough’.

Explore the process notes of converging the problem space on Miro

References

Choi, G. W., & Seo, J. (2024). Accessibility, Usability, and Universal Design for Learning: Discussion of Three Key LX/UX Elements for Inclusive Learning Design. TechTrends, 68(5), 936–945. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-024-00987-6

Corbin, T., Bearman, M., Boud, D., & Dawson, P. (2025). The wicked problem of AI and assessment. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 0(0), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2025.2553340

Dorst, K. (2011). The core of ‘design thinking’ and its application. Design Studies, 32(6), 521–532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2011.07.006

Eaton, S. E. (2023a). Postplagiarism: Transdisciplinary ethics and integrity in the age of artificial intelligence and neurotechnology. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 19(1), 23, s40979-023-00144–1. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-023-00144-1

Eaton, S. E. (2023b). The Academic Integrity Technological Arms Race and its Impact on Learning, Teaching, and Assessment. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology, 48(2). https://doi.org/10.21432/cjlt28388

Google. (2025). Gemini (Flash 2.5) [Large language model]. https://gemini.google.com/

Khlaif, Z. N., Alkouk, W. A., Salama, N., & Abu Eideh, B. (2025). Redesigning Assessments for AI-Enhanced Learning: A Framework for Educators in the Generative AI Era. Education Sciences, 15(2), 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15020174

Norman, D. A. (2013). The design of everyday things (Revised and expanded ed). Basic Books.

Ostafichuk, P., Hodgson, A., & Fengler, M. (2019). The engineering design process: An introduction for mechanical engineers (Third edition). Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of British Columbia.

Sabbaghan, Soroush. (2025, November 19). Designing for Integrity: Learning and Assessment in the Postplagiarism Era [Video]. https://yuja.ucalgary.ca/v/designing-for-integrity

Schön, D. A. (2013). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Ashgate.

Welch, B. (2024). Demystifying Writing: Collaborative Rubrics and Process-Based Feedback. American Association of Philosophy Teachers Studies in Pedagogy, 9, 128–148. https://doi.org/10.5840/aaptstudies202472288