This podcast is a dive into what holds people back from an experience that they themselves want to do. It explores moments of when it happens, then with a lens of neuroscience, and ultimately extends these ideas into how educators can help people overcome their hesitations.

Listen:

Podcast Transcript

Today we are going to look into engagement with experience and in particular why people don’t engage with experience. Taking us through this journey we have four acts. One, a short story. Two, about the value of performance. Three, the mind on the edge. And Four, strategies to overcome the edge.

Act 1 – Cliff Jumping

We are in Lynn canyon, in North Vancouver, a beautiful park filled with dense evergreen trees, intertwining trails, and a small creek that has carved its way through the landscape, at times with cliff walls on either side, higher than 100 feet. To me this is a very special place that has shaped much of my personal perspectives of the inhibitors to experience.

When I was growing up I would come in the summer time with my friends to jump off some of these cliff walls into the water below. Imagine taking an elevator up to the forth floor, stepping out onto the balcony, and looking straight down into water below. You feel your hear t beat louder, and your breath deepen. You are in defiance of your very own self-preservation instincts. But for some reason you made a choice to climb up to this very spot with the intention to jump, and you thought you already made this decision to jump, but you still haven’t jump, you’re still there, frozen. Stubbornly frightened or confused? You feel the pressure of your goals, maybe your identity, or the social pressures from your friends or onlookers. And you know it only takes one step and this agonizing anxiety would be over and you finally do make that choice.

And you fall. You watch the world fly up above you. But still you’re nervous, bracing for the water. Finally, the water. And you’re under it, finally at equilibrium. And then at rest on the shore and you’re exhilarated. You’re ready to go again, and with less contemplation.

And the why was this something you want to do is still not really understood. Is it the feeling of falling? the pride? The overcoming of a challenge? The person that you want to be? This all feeds right back as bits of motivation to step up to that ledge and jump.

And that moment right on the ledge, that agonizing time spent standing there, looking down at the water is the question. Because each day students step up to the metaphorical ledge of education and they don’t jump. They remain on the ledge as educators, designers, and even the students themselves may not know how they couldn’t take that step off the ledge and immerse themselves into the experience of learning.

So in exploring this question, I look at the value in overcoming this moment, what may be occurring in the mind at this moment, and strategies of overcoming the edge and jumping in.

Act 2 – Performance

The act of performing or the doing of something can be the very learning experience itself. Vygotsky’s concept of the Zone of Proximal Developmment explains that one may learn when pushed just beyond what they can do on their own so long as there is adequate support to do so. Cazden (1981) elaborates that “the teacher assumes that the assisted performance is not just performance without competence, but performance before competence–that the assisted performance does indeed contribute to subsequent development.”

In cliff jumping, or facing a fear, once you jump, it’s so easy to go again. The performance of jumping, maybe, has taught your brain that it is indeed safe and your fear is unmerrited. So right away, you may want to jump again and this time, your fear is less of a barrier. This mirrors the technique of exposure therapy where distressing stimuli are performed in a safe environment with the intention of linking the stimuli with positive outcomes instead of distress.

But what if the real life individual feels like a different person than the one performing?

In the world of show business, actors and actresses become characters. Scott (2017) explains that there are opportunities for liberating transcendence from the self and into a character. One where the I is no longer and one becomes something new, free from the normal self-judgement among other things.

And this feels good – maybe the cliff jumper mid-air is a different person than the one on the edge? The inter family systems model views the mind to be subdivided into different parts (IFS Institute, n.d.). Not dissimilar to the Disney Pixar movie Inside Out **** Inside Out Audio ***, though these parts are not always divided by feelings like in the movie. Maybe using a different part of your mind feels like being a different person.

Scott elaborates on the psychological concept of ‘edgework’ – hilariously the term originally comes from the late Hunter S. Thompson who founded ‘Gonzo Journalism’ where the journalist immerses themselves so fully into their subject that they become a central figure. You see the overlap?

Now edgework is pushing the boundaries and testing the limits of the self often including voluntary risk-taking activities (Scott, 2017). “Surviving these results in feelings of triumph, joy and a heightened sense of self: participants describe feeling ‘pure’, ‘alive’, and hyper-real, experiencing self-mastery and self-determination.” (Scott, 2017).

There are a significant overlap of edgework with the theory of flow – being a state of intense focus and concentration on a narrow perceptual field (Scott, 2017). Like edgework, flow also allows for euphoria, a lack of self-judgement, and a type of divide between the ‘normal’ person and one in flow (Scott, 2017). Where flow and edgework differ is in the essence of risk – flow focuses on balancing skill with challenge, while in edgework, risk is sought out as an end of its own (Scott, 2017).

Cliff jumping is both a practice of edgework and flow since risk is an end of its own but that risk (if you’re not stupid) is a calculated one where the challenge is appropriate for your skill.

If you haven’t already made this link, I want to throw it in just for you! Because there is interesting overlap with video games as players take on the role of characters and act significantly differently than they do in real life. In the game world, the player as a character may commit heinous acts of violence (to name one thing), but in the real world that player may be non-violent. The self and the character one takes on is divided.

Act 3 – The Mind on the Edge

Maslow in 1958 explains the unconscious, ‘primary-processes’ of one’s mind as having “no negatives, no contradictions … [as] it is independent of control, … inhibitions, … calculations of possibility or impossibility”. From this portion of ourselves, we gain the ability to play, fantasize, and be creative (Maslow, 1958). In contrary, the conscious, ‘secondary-processes’ of one’s mind is “logical, sensible, and realistic.” On the edge, the ‘primary-process’ has no inhibitions and maybe just wants to play, to jump, while the conscious, ‘secondary-processes’ of ones mind may be calculating the risk and instilling fear. Much has changed in our understanding of the human psyche since 1958, but the concept of a split mind, with at times contradicting ideas, still remains.

With the notion of the performer becoming a different character than the person’s true self, this would mean that overcoming the edge is a process of overcoming the conscious, ‘secondary-process’. While being stuck on the edge is the secondary process taking over (Maslow, 1958).

Scott (2017) explains in show business, stage fright, “a state of existential self-doubt”, similar to the edge, can occur before or during a performance. During the performance, there may be a “disruption of the social frame” which exposes the actor or actress as their real self instead of a character. In Maslow’s concept,

These different parts within one person, the one on the edge or the jumper, the actress or character, the creative mind or the one of self-judgement may also be explained through the theory of cognitive load which views a limited capacity of working memory (Fisch, 2017). The brain, being very complex, has many different neural pathways, but only so much of it can be activated at one time. One unable to leave the edge may be ‘stuck’ in one mode of thought. Maybe ‘stuck’ in anxiety, fear, or self doubt.

Steele (2011), explains a study by Krendl, Richeson, Kelley, and Heatherton, “who used fMRI imaging technology to examine stereotype threat’s effect on brain activity.” They tested women who were strong math students to perform a math problem while examining their brains (Steele, 2011). The experiment group were put under stereotype threat by being told that “research has shown gender differences in math ability and performance” (Steele, 2011).

“Although women [not under stereotype threat] recruited neural networks that [from previous research] are associated with mathematical learning, women who were [under stereotype threat] did not recruit these regions, and instead revealed heightened activation in a neural region [that from previous research is] associated with social and emotional processing” (Steele, 2011). The women under stereotype threat did not perform as well as the control group enacting a great example of cognitive energy being wasted on extraneous details rather than the problem (Steele, 2011).

The mind on the edge may be viewed as a mind stuck in an inadvertent self-sabotaging cognitive process.

Act 4 – Strategies to Overcome the Edge

For some people, sometimes, the strategy is simple. Like Nike’s slogan and this, Shia LaBeouf’s ludicrous motivational speech: “Just do it”

Now it’s not that simple all of the time, so we’re going to explore some strategies that have come up from our ideas today. We will touch on motivation, invitation, scaffolding, characters, rituals, deception, and disinhibitors.

This isn’t meant to be an exhaustive list but instead more tools for the educational designer’s tool box.

Motivation

Why should someone jump off the edge? The act of performing may be the learning – the notion of performance before competence (Cazden, 1981). If the student truly believes this, it may be motivation in itself.

There are also strategies of appealing to intrinsic motivators within the learner or if needed, extrinsic motivators. I’m sure you know much of this so we’re going to move on.

Invitation

Does the learner perceive that they belong in the experience? Is it inviting? Or does it appear to be not for them?

Steele (2011) talks about cues in an environment. Cues of prejudice like “are some groups disdained”? (Steele, 2011) And the more subtle cues of contingency – do the educators “value the experiencing of group diversity as integral … to one’s education?” (Steele, 2011) In other words, does the learner perceive that the educators strive for diversity or inclusivity of their group?

One concept Steele (2011) explains is of ‘critical mass’, a tipping point where once a significant amount of representation is achieved, identity or stereotype threats subside.

So for an environment to be inviting, it must be free of prejudice and contingency cues, ideally achieving a critical mass of the minority one wishes to include. Put simply, does the person see themselves in the experience or environment of the experience. Are they represented?

Now an educational technology designer may ask can an environment be inviting to everyone? Or does a designer need to choose who they are designing for?

Scaffolding

Scaffolding is the act of stripping the experience into smaller learning experiences that the learner conducts one at a time. It’s as if the edge starts at a comfortable, undaunting height, and once successfully completed, the edge will be raised higher or supports will be removed. This iterative approach ends with the student on that high edge, but now they are practiced with skills and they know how to navigate the experience and overcome the edge.

This approach is a constructivist one, aiming to keep the student within that zone of proximal development where they are working just beyond their skill (Powell & Kalina, 2009). With this properly matched skill to challenge level, there is the opportunity for flow.

Characters

Can educators directly recognize the different parts of a learner’s brain? Maslow (1958) and Steele (2011) describe that when one uses a different part of their brain, their thinking and actions may be very different. So how could the use of characters (or becoming a different person) affect education? How can educators help students assume a different character, something more successful than just asking students to “put on your math hat.“

Fullerton (2018), speaks of characters in video games as having abilities, characteristics, and oftentimes a story. Getting a learner into a character may need some creativity from the educator.

Rituals

Some performers enact rituals prior to a performance to create a “faux-confidence through the illusion of gaining control” or to bond performers (Scott, 2017). Some rituals range from superstitious to playful and fun such as meditation, Eskimo kissing, and sharing irrational beliefs (Scott, 2017).

Some pre-event rituals, such as this jingle before streaming on Netflix **** Netflix Sound *** elicits a pavlovian-like response.

Can educators utililze rituals to get students ready for an educational experience?

Deception

Deception would be the hiding of the edge or turning focus away from it.

This may be imagining the audience to be only in their underwear, to deflate their critical power Scott (2017). Potentially unethical, but an educator may withhold information from the learner that would make them ‘waste’ their cognitive load and make them very evident of being on the edge – if you’ve read the Sci-fi novel, Ender’s Game, I don’t want to give it away, but it comes to mind as a great example.

Disinhibitors

Scott (2017) explains that some actors/actresses turn to alcohol, tobacco, or other substances to help them overcome stage fright. Substances can quite easily allow someone to take on a different part of their mind, to feel like someone different.

Another trend is the use of ‘study drugs’ that allow one to focus.

I’m not suggesting we should get all our students drunk but instead to imagine a time and a place where it may help an educational experience.

I’m going to play you this clip from Freakenomics, where Yahuda explains a counselling practice where the client is under the influence of MDMA (also known as Ecstacy).

“If you’re put in the exact right state where you’re not afraid of your emotional reactions or your memories, you have maximum interpersonal trust, a minimum self-blame or guilt or any of those things. This is the state that is a perfect place to be to start processing very difficult, traumatic memories and really catalyzing a therapeutic process …

And you might ask, “Why do you need a drug to catalyze a therapeutic process?” And the metaphor that’s often used is that psychedelics to the mind are what the telescope is to astronomy and what the microscope is to biology. It’s not that all of a sudden you see things, you’re hallucinating things that didn’t exist or that aren’t real. You’re actually allowing yourself to have a tool so that you can really see things that actually are there, things that are really important that aren’t that obvious or cannot be looked at in any other way. And so once they started to understand that that was the purpose of MDMA, it really clicked into place as something that is very necessary.

Because trauma survivors with PTSD, they don’t want to look at their traumatic experiences. They don’t want to look at the reasons that they’re kind of stuck where they are. Because it’s very, very painful” (Yehuda, 2020).

Conclusion

I hope these ideas of the edge of experience are a helpful lens. Maybe they’re bringing up more questions than anything else. Some of these techniques may be difficult to apply to education but hopefully, they incite some interest. And I’m very curious about your thoughts on the matter.

You can find references and further readings online.

Adrian signing off.

Podcast References

Cazden, C. (1981). Performance before Competence. The Quarterly Newsletter of The Laboratory Of Comparative Human Cognition. 3(1); 5-8

Yehuda, R. (2020). In Podcast Dubner, S. How Are Psychedelics and Other Party Drugs Changing Psychiatry? (No. 433) [Audio podcast episode]. In Freakenomics Radio. https://freakonomics.com/podcast/how-are-psychedelics-and-other-party-drugs-changing-psychiatry-ep-433/

Docter, P., Del Carmen, R. (Directors). (2004). Inside Out. Pixar Animation Studios. Walt Disney Pictures.

Fisch, S. (2017). Chapter 11 – Bridging Theory and Practice: Applying Cognitive and Educational Theory to the Design of Educational Media. In Cognitive Development in Digital Contexts. (pp. 217-234) Academic Press. ISBN 9780128094815. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-809481-5.00011-0.

IFS Institute (n.d.). Internal Family Systems Model Outline. https://ifs-institute.com/resources/articles/internal-family-systems-model-outline

LaBeouf, Rönkkö & Turner. (2015). Shia LaBeouf “Just Do It” Motivational Speech. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZXsQAXx_ao0&ab_channel=MotivaShian

Maslow, A. (1958). Emotional Blocks to Creativity. Journal of Individual Psychology. 14(1); 51-56

Powell, K. C., & Kalina, C. J. (2009). Cognitive and social constructivism: Developing tools for an effective classroom. Education, 130(2), 241-251

Scott, S. (2017). Transitions and transcendence of the self: stage fright and the paradox of shy performativity. Sociology, 51(4); 715-731. ISSN 0038-0385

Setuniman. (2015). Intro 1L72. https://freesound.org/people/Setuniman/sounds/274787/

Steele, C. (2011). Whistling Vivaldi How Stereotypes Affect Us and What We Can Do . W. W. Norton & Company.

WikiPedia. (n.d.). Hunter S. Thompson. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hunter_S._Thompson

Problem

The challenge was to better understand how people engage with experiences, particularly in learning environments. When people approach experience, as was observed at Science World,1 there are multiple modes of engagement – some people dive in, others wait for instruction or invitation, and others will only observe. This raises the question of whether educational design should cater to these multiple approaches to engagement. I wonder:

- How do people engage with experience?

- What holds people back from experience?

- How can we help them overcome barriers to participation?

- Can we design ways for everyone to dive in?

- Is it best to let people engage how they want; to provide multiple modes for engagement?

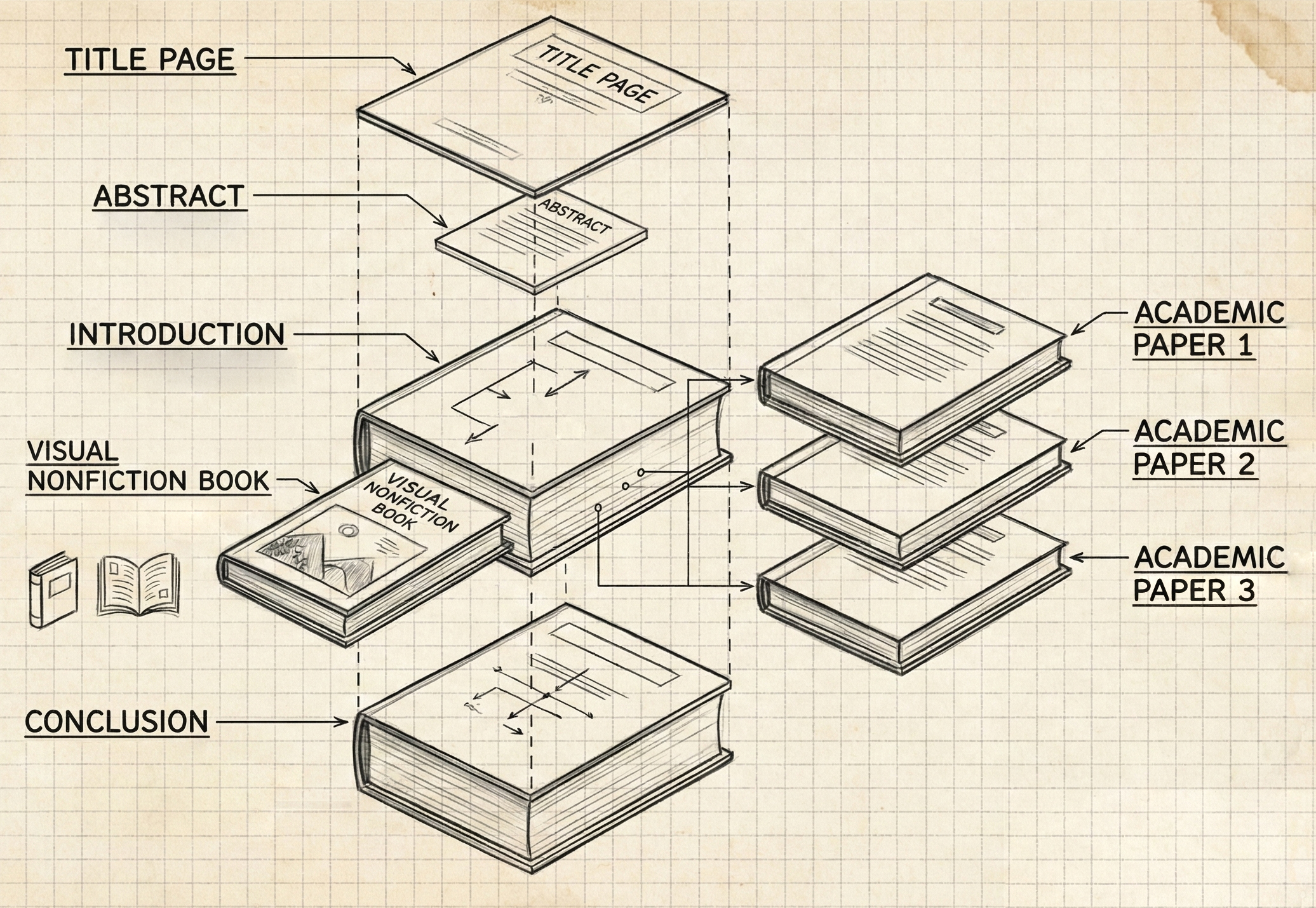

In sharing these findings, I set out to create a podcast—something I had never done before. This required not only researching and developing content but also learning the technical aspects of podcast production, including audio recording, editing, sound design, and crafting a compelling narrative.

This project is part of a self-designed course titled ETEC 580: The Learning Cookbook. As a student of the Master of Educational Technology2 program at the University of British Columbia, I had the opportunity to design a course based on my personal inquires.3 I found advisors and proposed my course that explores the multitude of aspects of experiential learning.

Action

To explore these questions, I approached the research from multiple angles. I examined theories on risk-taking and identity shifts, such as performance-before-competence and edgework, to understand how stepping into an experience can shape engagement. I also investigated cognitive and emotional barriers—Maslow’s dual-process thinking, cognitive load theory, and stereotype threat—to uncover why people hesitate to participate. Finally, I looked into practical strategies, including motivation techniques, scaffolding, role-playing, rituals, and environmental design, to see how educators can create conditions that encourage immersion.

To bring these ideas to life, I wrote a transcript that blended narrative storytelling with research insights. Drawing inspiration from podcasts like Radiolab,4 Freakonomics,5 and especially This American Life,6 I aimed for an engaging and accessible style. I recorded and edited the podcast using Audacity,7 an open-source digital audio editor and recording application, incorporating free sound effects to enhance the audio experience.

Learnings

This project deepened my appreciation for the interplay between research and medium. Creating a podcast required distilling complex ideas, which I usually share through academic style writing, into accessible yet meaningful insights while maintaining an engaging narrative flow. This balancing act mirrored the broader challenge of educational design: how to present information in ways that encourage participation without overwhelming the learner.

A key lesson was the value of iteration. Crafting a script that synthesized research while keeping listeners engaged took multiple revisions, refining both content and storytelling. At the same time, learning audio recording, editing, and sound design added another layer of complexity, reinforcing the importance of designing intuitive and inviting experiences.

Application

The research uncovered strategies that can enhance experience design, education, and teaching. By examining how people engage with new experiences—whether by diving in, waiting for instruction, or observing from the sidelines—the project revealed ways to reduce hesitation and encourage participation. Neuroscience and psychology offer insights into the cognitive and emotional barriers that hold people back, such as cognitive load, stereotype threat, and risk perception. Understanding these factors can help educators design learning environments that feel safer and more inviting.

Some strategies to promote engagement with experience, which are explored further in the podcast, include:

- Motivation

- Invitation

- Scaffolding

- Characters

- Rituals

- Deception

- Disinhibitors

Footnotes

- Science World is a charitable non-profit and science centre based in Vancouver, BC that engages learners across the province in STEAM (science, technology, engineering, art & design and math). https://www.scienceworld.ca/

- Master of Educational Technology. University of British Columbia. https://met.ubc.ca/

- ETEC 580: Directed Study / Problems in Education. Master of Educational Technology. https://met.ubc.ca/courses/etec-580/

- Radiolab is a radio program and podcast produced by WNYC, a public radio station based in New York City. It focuses on topics of scientific, philosophical, and political nature, presenting them in an accessible and engaging manner. https://radiolab.org/

- Freakonomics Podcast is a popular American public radio program and podcast that explores socioeconomic issues and presents them in an engaging and accessible way for a general audience. https://freakonomics.com/series/freakonomics-radio/

- This American Life is a weekly public radio program and podcast that explores a different theme each week through various stories. https://www.thisamericanlife.org/

- Audacity. https://www.audacityteam.org/